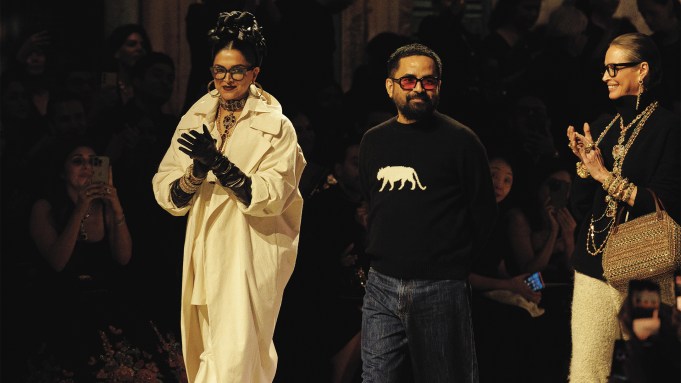

“I heard 78 million rupees crore ($9 million) was spent,” whispered an Indian fashion insider over chai at one of Mumbai’s most exclusive private clubs. It was Sunday evening, and on the manicured lawn, in the shadow of the Ambani family’s 27-story compound, everyone was buzzing about “Sabya’s” 25th-anniversary fete, which had taken place the night before. It seemed as though tout le monde had descended upon Mumbai, with 700 well-heeled guests that included Bollywood star Deepika Padukone and supermodel Christy Turlington Burns (who opened and closed the runway show, respectively), business titan Anand Mahindra and actor Siddharth, plus a bevy of billionaires and defunct royals who dusted off their most glittering jewels for the occasion. And every one of them was clamoring for a moment with the man of the hour, designer Sabyasachi Mukherjee, who in typical fashion was milling about in jeans, sneakers, and a cashmere sweater emblazoned with his eponymous brand’s Bengal-tiger logo. It was a striking contrast amid a sea of strictly black formal ensembles, which Mukherjee had requested—the better to show off his own colorfully ornate wares on the runway.

An ordinary runway it was not. After making their way through an alleyway of hanging laundry, guests were transported to Mukherjee’s native Kolkata, courtesy of an elaborate set for which no detail was spared, down to the chipping paint, dusty stained-glass transom windows, and drooping electrical wires. To the untrained eye, it was a picture of faded grandeur. But for Mukherjee, India’s glamour never left. “Luxury exists in the poorest of Indian homes. It is in our sub-conscious,” he explains. “Even if they cannot afford real jewelry, people will wear flowers in their hair.”

Designer Sabyasachi Mukherjee in his Mumbai home.

Sunhil Sippy

Sabya, as he is lovingly referred to by his millions of fans, has proved himself to be equally resourceful. Often dubbed the Ralph Lauren of India for his distinctly Indian yet instantly recognizable aesthetic (“That’s so Sabya!”)—which extends from his fashion collections for men and women to his stores to his fine jewelry—the 51-year-old is by far the most famous and celebrated designer in the South Asian nation of over 1.4 billion, an unrivaled champion of its rich artisanal traditions, and quick to tell you he’s just getting started. After having made a splash in New York with his evocative boutique and a slew of high-profile collaborations, he is increasingly attracting the attention of fashion observers in the West. And it all began in a middle-class Bengali household.

I’m a proud Bengali, and in our part of the country, our real currency is culture.

The son of a chemical engineer and an art teacher who had aspirations for him to become a doctor or an engineer, Mukherjee had other plans. Curious about the world, he stowed away on a train at the age of 15. To fund his studies at India’s National Institute of Fashion Technology, he took a series of odd jobs that included washing dishes in Goa. Upon his graduation, his younger sister, Payal, loaned him the equivalent of $200 to kickstart his business. Mukherjee used the seed money to purchase a sewing machine, a bucket, and some dyes for hand-coloring fabric scraps procured from local markets (though he clarifies they were remnants of precious antique textiles). Today, the brand is reportedly on pace to become a $2 billion enterprise by 2030.

Maximalist looks in jacquard and faux shearling from Sabyasachi’s 25th-anniversary collection, photographed in Kolkata.

Sunhil Sippy

Initially, he lacked sufficient funds to pay a salary to his pattern maker. When the man interviewed for the job, Mukherjee recalls, he said, “You look very wise, and I think you’ll have a remarkable business, so you don’t have to give me an advance.”

Mukherjee was equally confident in his abilities. “I always knew I would be one of the big designers,” he says. “I remember when my father asked me what I was doing with my life, I just sat him down, looked him in the eye, and said, ‘Don’t worry, give me five years, and I’ll prove you wrong.’ ” Though it wasn’t a straight shot to fame.

In 2006, having achieved moderate acclaim in India and following an auspicious moment when his work landed in the window of Browns—legend has it that if your wares are displayed there during London Fashion Week, you’ll have great success (see John Galliano and Alexander McQueen)—Mukherjee arrived in New York like so many young designers keen to make their mark, only to be told that his clothes were “too Indian” for the U.S. market. He stuck it out for a year and contemplated changing his aesthetic. Then the eminent fashion journalist Suzy Menkes intervened, advising him to return home. Mukherjee remembers her saying, “I don’t understand you, Sabya—you have such an important emerging market that you can be the king of. Why do you even want to come to the West right now? Pack your bags, go back, and start working in India. When you have power and position, come back to America, start dictating your terms, and everyone will listen to you.”

A gold fil coupé dress in Sabyasachi’s 25th-anniversary show; the jewelry salon in the brand’s Manhattan boutique.

Dolly Devi/Björn Wallander

Mukherjee immediately knew what had to be done: He began sketching a bridal collection on his flight home, with Bridal Fashion Week only a month away. Titled Chand Bibi, it was an homage to traditional Indian bridal attire at a moment when many women in the country were eschewing time-honored sartorial customs. “Indian women shouldn’t be forced to don Western wear due to peer pressure or because the traditional look is tagged as ‘tacky,’ ” the designer told the Times of India back then, citing Japan, Spain, and Italy as countries whose fashions preserve their culture. The collection was a critical and financial success and made Sabyasachi a household name in his home nation. A decade later, he (along with Ralph Lauren) would be responsible for outfitting Priyanka Chopra and Nick Jonas for the couple’s 2018 nuptials. Last summer, he not only dressed many of the guests at Anant Ambani’s much-covered wedding to Radhika Merchant, but he was also responsible for Ambani’s gold-embroidered sherwani, made even more fabulous by its emerald buttons.

Yet despite the fame and fortune that traditional wedding attire has afforded Mukherjee, times are changing. These days, a growing number of young Indians are choosing more modest weddings (if they’re marrying at all), preferring to spend their funds on what they deem more worthy pursuits, such as building start-ups. And while many at the anniversary gala may have been surprised not to see a parade of lehengas, it’s all part of the plan—and probably a wise one given that Sabyasachi’s biggest outlet abroad is New York’s Bergdorf Goodman, the temple of Euro-centric high fashion. “I told Mr. Birla that we will likely never see the full potential of this business in our lifetimes,” he says, referring to Kumar Birla, the billionaire chairman of multinational conglomerate Aditya Birla Group. “We are building this business for the next 100 years.” Birla’s firm has invested a sizable sum in Sabyasachi, and the designer has infused his ready-to-wear lines for men and women with Western silhouettes distinguished by couture-level embroideries and embellishments; the latest collection signaled a greater focus on menswear, which Mukherjee felt was overdue for a shake-up. The brand has also made a brick-and-mortar push, including the 2022 opening of its Christopher Street store.

His and her suiting at the designer’s recent Mumbai show; high-jewelry choker in 18-karat gold with morganites, tourmalines, tanzanites, and brilliant-cut E-F VVS and VS diamonds.

Dolly Devi/Sunhil Sippy

During New York Fashion Week last September, the cocktail party the designer held at the shop was arguably the hottest ticket in town—and there wasn’t even a runway show. Numerous editors in chief made the pilgrimage, as did Martha Stewart, Carolina Herrera, and jewelry designer Prince Dimitri of Yugoslavia, all wending through the thicket of beturbaned waitstaff plying guests with Dom Pérignon and caviar blini to admire the baubles in the high-jewelry salon. It’s not just a store but a statement: Mukherjee is not looking for validation from the West. Far from it. “India has such gifts to give to the world, and my biggest worry is that we will lose them,” he says, pointing out that despite the popularity of one Italian brand known for its paisley prints, the roots of those designs are in Kashmir. “What I did was create a global collection with an Indian soul.”

Despite the opulence of it all, Mukerjee’s aesthetics are informed by his solidly middle-class roots. Take a closer look at the designer’s high-jewelry pieces and you’ll see chrysoprase or sodalite mingling with sapphires and diamonds. “I’m a proud Bengali, and in our part of the country, our real currency is culture,” he says. “We don’t discriminate things according to their price. We choose them according to their vibrancy or how the raw material speaks to us.” Ditto the New York store, which, looking beyond the 30 chandeliers and antique Kashmiri-paisley-clad walls, is an ode to the “showcase” found in typical Bengali homes. A sort of cabinet of curiosities, it serves as a daily reminder of the evolution of the owner’s life and can include anything from a piece of wedding china to an empty jar of cold cream, offering visitors insight into the family’s lives.

Men’s and women’s looks from Sabyasachi’s 25th-anniversary collection.

Dolly Devi

The unapologetic mingling of things precious and humble comes naturally to Mukherjee, who is wearing a long-sleeve Uniqlo T-shirt when we speak and credits his two wildly different grandmothers with being his original and constant muses. He dedicated his 25th-anniversary show to the two women. “My work is my maximalist maternal grandmother. I am my minimalist paternal grandmother,” says Mukherjee, who confesses to having a tightly edited wardrobe and an aversion to souvenirs. The former had a husband “who spoiled her silly” with jewelry, brocades, and saris; the latter, of limited means, was a staunch vegetarian who practiced yoga each morning and led a more spiritual life. “I don’t have scrapbooks or even family photographs, but my brand is the opposite of me.” What he learned from both women was centered more on values than on the actual value of material items. “Maximalism can go horribly wrong if one doesn’t strike the right balance.” For every Alessandro Michele or Iris Apfel, there are countless disasters.

My sense of tailoring is almost like a cross-cultural intervention between British tailoring and Indian tailoring.

Another influential woman in Mukherjee’s life is Linda Fargo, Bergdorf Goodman’s chic, silver-haired senior vice president of fashion—and the retail high priestess responsible for Sabyasachi’s Big Apple debut. Though the store is not the only American retailer with which Sabyasachi has collaborated, it has been perhaps the designer’s biggest champion, beginning in 2020, when it hosted the brand’s stateside fine-jewelry launch. “We had them at hello,” says Fargo of Bergdorf’s jewelry clients. She had first visited Mukherjee that year, on the occasion of his company’s 20th anniversary. “At that time, the ready- to-wear was almost like a little bit of a side thing, but I didn’t want to let the moment slip away, so we started with the jewelry.” Jewelry, it turns out, currently accounts for about one third of Sabyasachi’s sales, and it’s a category Mukherjee expects will continue to grow, despite many pieces being priced well into the millions of dollars. The designer has subtly tweaked some of the pieces to appeal to the American market, as women here favor lighter-weight earrings than those traditionally worn in India. Earlier this winter, Bergdorf opened a dedicated Sabyasachi boutique on its fourth floor to showcase the brand’s leather goods and ready-to-wear, and last spring, the designer hosted a signing event for the lipstick he created with Estée Lauder. “I told Jane Hudis (executive group president at the Estée Lauder Companies) that I had only one demand: that we try to make the best lipstick in the world. She asked if I thought my market was ready for that. I said yes, it is.”

A menswear look from Sabyasachi’s 25th-anniversary collection; The Moulin Rouge high-jewelry necklace in 18-karat yellow gold with tourmalines, pyrites, iolites, sapphires, spinels, and E-F VVS and VS diamonds.

Tarun Vishwa/Sunhil Sippy

So long was the line along West 58th Street that Mukherjee himself paid to keep the store open an additional hour to ensure that everyone was seen to. Many of the customers were Indian American—part of the wealthiest immigrant group in the United States—but plenty of others were not, signaling Sabyasachi’s growing presence stateside. The product sold out globally in three days. “What people get wrong about India is the assumption that India likes to buy cheap. That’s a patently false statement,” he says. “Indians appreciate value, and they will open up their wallets as long as the value doesn’t drop.”

Value is a frequent topic of discussion at the company and one that often gets silenced in the luxury market, particularly where more maximalist aesthetics are concerned. “When you’re doing maximalism, the first question that comes up is cost. No one really talks about quality or value,” says Mukherjee of overly embellished, overpriced garments that often mask shoddy construction. For customers of the brand, Sabyasachi-style value means painstaking attention to detail, such as hand-embroidered and -painted jacket linings designed purely for the pleasure of the wearer—and not just for women. The same level of care is given to jewelry and handbags, where there’s always a precious element on both the inside and the outside. And on the occasions that the designer collaborates, he chooses his partners carefully. That means Christian Louboutin for footwear (sneakers and smoking slippers encrusted with semiprecious stones and gold embroidery) and, most recently, New York–based bespoke-eyewear maker Morgenthal Frederics for a collection of sunglasses accented with enameling, rare woods, and discreet placement of the Sabyasachi-tiger logo. Mukherjee is developing a fragrance that reportedly will capture the essence of Kolkata; renowned French noses Frédéric Malle and Nathalie Lorson were both spotted at the gala.

The fastidiousness and reverence for craft is a much-needed balm for a time when a few high-ticket items actually feel worth the price. Sabyasachi’s products, by contrast, seem like future heirlooms. Luxury, in Mukherjee’s view, is anything that is made beautifully by hand without regard to time—the ultimate resource. “We are losing our heritage,” he says, “and luxury is going to be about bringing back that heritage, which can only be brought by the intervention of the human hand.”

A womenswear look from Sabyasachi’s 25th-anniversary collection; a high-jewelry necklace.

Dolly Devi/Sunhil Sippy

“We do three jobs at Sabyasachi: One job is innovation, the other is restoration, and the third job is to sensitize our younger customers, who might not have seen the richness of the vibrancy of India that their grandparents or their parents have seen, so that it puts a desire in them to be able to own and be a part of that heritage,” he notes, adding that the brand’s retail spaces function a bit like living museums, should any know-how ever be lost. “The most important thing will be provenance, because who are you going to buy your kimono from? A company in Paris?”

Today, the craftspeople whom Sabyasachi contracts are thriving in part because the brand has committed to training the next generation, who grew up watching their parents struggle. But thanks to renewed appreciation for Indian craft (and in no small part to the fashion industry), those parents are now building homes, buying cars, and, in some cases, even have electricity for the first time. Several have started direct-to-consumer businesses with the help of their children, many of whom had moved abroad in search of better opportunities but are returning home armed with the marketing and supply-chain knowledge to help scale their small family businesses. Much like the Sabyasachi brand, there’s an immense respect for tradition but an eye toward the future.

For the 25th-anniversary collection, that meant a stronger focus on menswear than in the past, with influences as wide-ranging as M.C. Hammer, Hamish Bowles, Jawaharlal Nehru, and the Prince of Jodhpur. Bow blouses, pearls, and metallic-flecked-tweed separates challenged traditional notions of masculinity in a place where, despite the general exuberance, men are expected to favor blue, and women, pink. “All my clients who are mourning Dries Van Noten now have somewhere to shop!” stylist Nolan Meader rejoiced at the post-show party, praising the unique textiles on display, such as an embroidered tulle that mimicked tweed.

The Mangrove high-jewelry bracelet in 18-karat yellow gold set with multicolored gemstones and

E-F VVS and VS diamonds.

Sunhil Sippy

Much of the tailoring in India has maintained its historical British lean, says Mukherjee, recounting a story of meeting a friend who was concerned he was underdressed for dinner. “What do you mean?” the designer asked. It was Mukherjee’s button-front shirt. “In India, everybody wears a button-down shirt, from someone selling fruit on the street to a person cleaning your toilets to an executive sitting in a boardroom. That’s when the penny dropped.” He realized that menswear was overdue for a refresh.

“My Indian customer is quite conservative (outside of the weddings realm), but I am seeing a lot of non- Indian men in America gravitating towards my menswear,” he says. They’re part of the global shift of men taking far more risks with their clothes. For Mukherjee, the time he now spends in New York and the prevalence of streetwear have been eye-opening. “My sense of tailoring is almost like a cross-cultural intervention between British tailoring and Indian tailoring.”

Notably, many of the tailored ensembles that featured in the 25th-anniversary show were presented on men and women side by side, on equal footing. “I’m the one who gets the glory, but I have been steered in my professional career by a band of unflinching women who pushed me towards the destiny that I enjoy today,” says the designer, reflecting on the past two-and-a-half decades. “It’s quite something for a man to be pushed by women to do his best, because I come from a country where there’s an overarching patriarchy. My brand was created by women who pushed me forward.” His sister, Payal, who 25 years ago provided the seed money, worked on the design team until recently.

Sabya’s “showcase” of antiques in his Christopher Street store.

Björn Wallander

Despite the fanfare and the ambitious goals, it’s not all full speed ahead for Sabya, who refuses to fall in line with Western fashion houses’ strict adherence to seasons and says it could be as long as two years before he stages his next show (it had been five since his previous one). Fear not: You can order select pieces from past collections. “You don’t build a sustainable business with greed,” he says.

Mukherjee is supremely confident in the brand’s potential, yet also remarkably humble, insisting that he is still the same scrappy, fearless teenager who spent three nights in a Mumbai train station. And he still remembers his parents’ worrying about how they were going to feed a family of four when his father lost his job. “That level of poverty can either scar you for life, and you’re going to be always scared of not having money, or it evolves you to realize that money is so transient that it’ll come and go,” he says, noting that while he wants to run a successful business, he has no financial “obsession.” “When you learn to detach yourself from money, you learn to take a lot of risks that your heart tells you is the right thing to do, and I have always followed my instinct.”

As for his mother and father? “You know, they look at me and say, ‘Fine, we saw you on television. We’re very proud of you, but we would have been prouder if you had been a doctor.’ ”