new delhi

CNN

—

As air pollution worsens in India’s capital, parents are faced with an impossible choice: stay or leave.

Amrita Rosha, 45, is one of those who chose to flee with her children. Vanaya, 4, and Abhiraj, 9, are suffering from respiratory illnesses due to increased pollution and require medication.

“I have no choice but to leave Delhi,” Rosha, a housewife who is married to a businessman, told CNN from her home in an affluent area of south Delhi last month as she completed the final preparations before leaving for the Gulf state. told. Oman.

Every year for the past decade, smog blankets Delhi as winter approaches, turning day into night and disrupting the lives of millions of people. Some, especially young children with underdeveloped immune systems, are forced to seek medical attention for breathing problems.

Rosha makes sure her children have access to the best medical care, including doctor visits, steamers, inhalers and steroids, and travels to the outskirts of Delhi to escape the stifling air.

Wealthy families like the Rochas are able to escape, but it’s a different story for those who don’t have the means to escape.

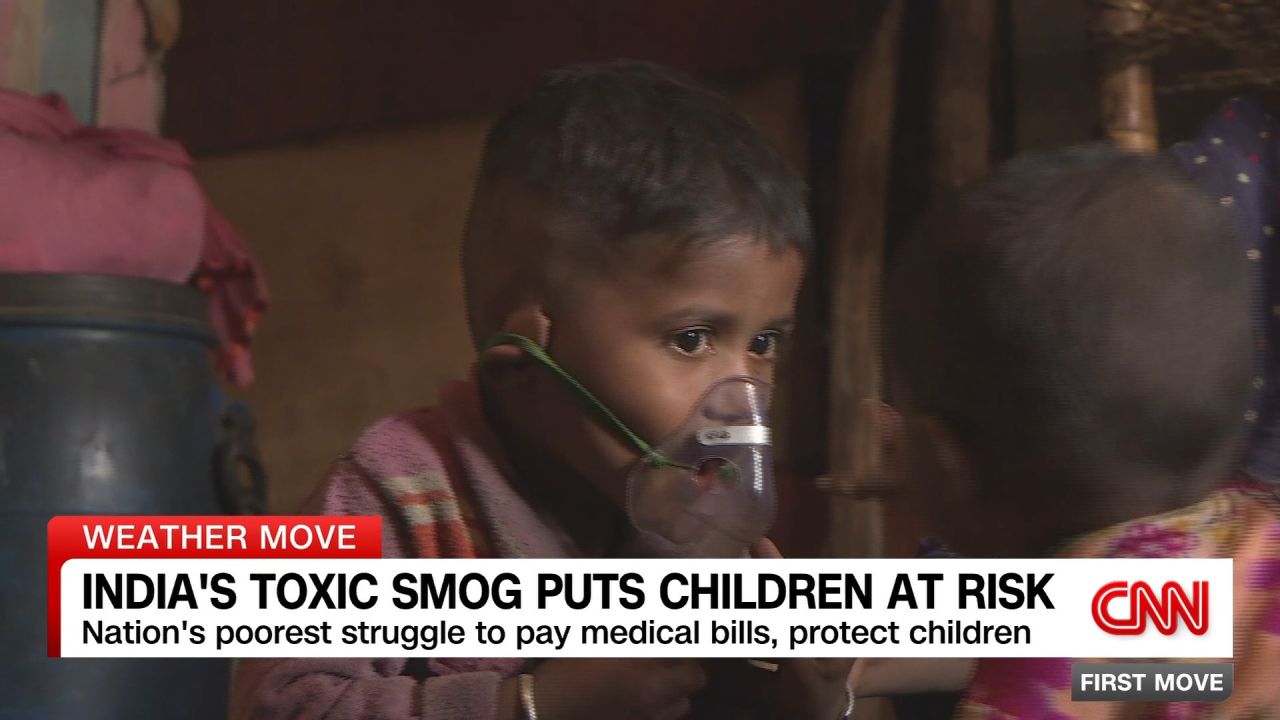

About 25 miles away in a Delhi slum, Mr. Muskan, who goes by his first name, picks up drops of medication left in a child’s nebulizer, a machine that turns liquid medication into a fine mist that is inhaled through a face mask or mouthpiece. looking at him worriedly. .

Mothers limit its use because they cannot afford more.

“We are giving half (the dose) of the medicine to our children,” she said of Chahat, 3, and Diya, 1. They each have been using nebulizers since the first winter. Born.

After weeks on the streets, Muskan bought a $9 nebulizer. She earns a living by picking up rags and other trash, and her husband is a daily wage laborer.

“When I see them coughing, I worry that my children are going to die. I feel bad because I keep worrying that something terrible will happen to them. ” she said.

The suffering of Delhi’s children is becoming more and more impossible to ignore.

“Children are having to rely on steroids and inhalers to breathe…The whole of northern India is in a medical emergency,” Atishi, the Delhi chief minister who goes by his first name, said last month.

The Supreme Court intervened to monitor measures introduced to curb pollution. Pollution is generally caused by factors such as vehicle exhaust, crop burning, and construction work, combined with unfavorable weather and climatic conditions.

This includes banning vehicles, demolition and construction work, and watering roads. Authorities have increased public transportation and cracked down on crop burning.

Despite these measures, Delhi remained the most polluted city in all of India in November, according to the Center for Energy and Clean Air Research.

Manjinder Singh Randhawa, a pediatric intensive care unit doctor at Rainbow Children’s Hospital, said he diagnosed a young child with asthma in a “very dangerous condition” for the first time this year.

India’s toxic smog puts children at risk

In the long term, pollution can have serious effects on the respiratory, immune and cardiovascular systems, he added.

CNN has reached out to the national and state governments and the Air Quality Control Board, which is responsible for maintaining air quality in the region, for comment.

Last month, pollution levels crossed 1,750 on the air quality index in some parts of Delhi, according to IQAir, which monitors global air pollution. A reading above 300 is considered a health hazard.

In recent weeks, pollution levels of PM 2.5 (tiny particles that can penetrate deep into the lungs) have soared to more than 70 times the health limit set by the World Health Organization. This week it was more than 20 times that level. Research shows that inhaling PM 2.5 can lead to cognitive impairment in children.

Some parents, like Deepti Ramdas, moved away several years ago to prioritize their children’s health. When her son Rudra was born three years ago, she never thought leaving Delhi would become a reality. However, things changed in January 2022, when he was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit.

Doctors told her to leave Delhi if she wanted her son’s lungs to develop, Deepti recalled. She had family in the southern state of Kerala, so she decided to go.

“It was not an easy decision. I had to quit a job that I loved…and my husband had to continue to stay in Delhi for work…so we became a long-distance marriage. ” she said.

However, Deepti was relieved to learn that Rudra had no breathing problems in Kerala. They visited Delhi in the first week of December to meet their father. “He is three years old now, so we were hoping that his lungs would get stronger, but within a few days Rudra started having seizures and we had to use a nebulizer again,” Deepti said.

“It was heartbreaking to see him like that. There was no way he could go back to Delhi,” she said, adding that Rudra had been playing outdoors in Kerala in October since he was hospitalized in 2022. I shared photos from the past.

Many parents in Delhi live with anxiety fueled by their inability to escape the city for work or other commitments.

“You can’t just do this. You have to plan and be lucky,” 29-year-old mother Uluvi Paraslamka told CNN. She said her daughter Reba, 2, has been using a nebulizer since her first winter.

When Arvi was pregnant, she recalled that her husband, Prateek Tulsian, reacted to news of environmental pollution by saying he would make sure there were enough air purifiers in the house to protect their child. . But nine months after giving birth, Reba had her first seizure.

“There was a lot of panic at the time. It was difficult to understand why she needed so many drugs. It was very scary. It took me a while to recover,” Prateek told CNN. told.

Irvie added: “I keep checking her temperature and don’t let her go out or eat anything that might make her symptoms worse. I’m now an overprotective parent. I did.”

When you hear Reva sneeze, you know she’ll start coughing, then her nose will get stuffy and she’ll need a nebulizer.

Mr. Irvey said he has decided to move to Guwahati in northeast India, where air quality is better, during next year’s high-pollution period.

“I was born and raised here and I live comfortably here. It’s not easy to make another home there, but we don’t have a choice,” she said.

Muskan and his neighbors in a Delhi slum aren’t so lucky.

She rushes to the shared nebulizer when her children exhibit symptoms such as chest pain, coughing or vomiting. Children ask for it themselves and use it with trained precision, she says. However, not everyone can afford to have a machine at home.

Some of her neighbors rush to the nearest private clinic and pay about 80 rupees, or $1, for each treatment.

One of them is Deepak Kumar, a daily wage worker with four children. His youngest and only daughter, Kripa, 1, has been using a nebulizer for two consecutive winters since her birth.

“The doctor told us to buy it, but we don’t have that money,” he said.

One doctor’s visit costs more than your daily wage.

Nights are the worst. When the doctor isn’t available, she relies on balms and steam to help her daughter get through the night. Even when she sleeps well, he wakes up with mounting debt from medical bills.

“Yes, I have a debt of 20,000 rupees ($235) and I will work even harder to pay it back,” he said.

Many like Kumar have come to Delhi from various parts of India in search of a better life, but are stuck.

“Living in the capital shouldn’t be that difficult,” he said.