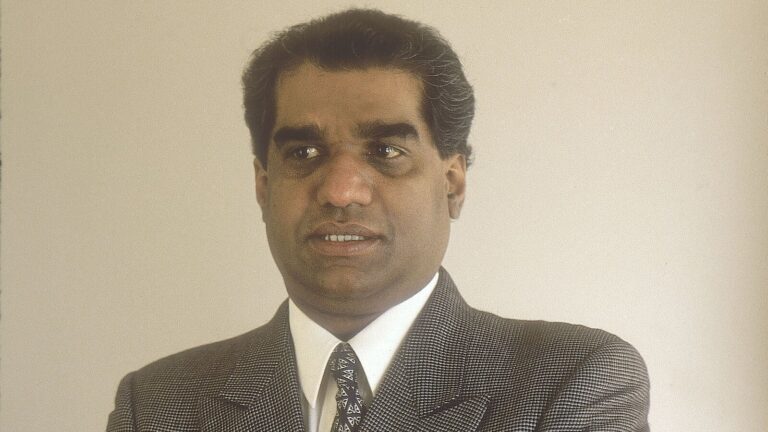

In its obituary, the New York Times called him “one of Asia’s most colorful businessmen.” This is a reference to his lavish lifestyle, which included a seaside house in Mumbai and a home in Holland Park, London, where he entertained politicians and other influential figures. I also loved Rolex and Dom Perignon.

early start

Like many other ambitious young entrepreneurs, the son of a cashew nut merchant was an early start. Just in his twenties, he invested in a hotel in Goa, where he made his first big buck. Shortly thereafter, he decided that India’s notorious licensing system, which reached its peak in the 1970s, was not conducive to the rapid growth he was aiming for, and moved his base to Singapore.

In collaboration with Canadian businessman Frederick Ross Johnson, who was then leading the American multinational Standard Brands, he founded 20th Century Foods, which sold packaged potato chips and peanuts. Although the startup didn’t make him much money, it endeared him to Johnson. Johnson was a central figure in the infamous Nabisco takeover battle, described in the fascinating 1990 book “Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Navisco.” Written by Brian Barrow and John Hellyer.

Impressed by Pillai’s sound judgment and deal-making ability, Johnson appointed him head of Nabisco Commodities, a division of Standard Brands. He did a good enough job that he was asked to run the Asian subsidiary of British biscuit company Huntley & Palmers.

This was the starting point for his secret meetings in India, as a British company had control of Britannia India. Pillai bought a stake in the company and is now running it successfully. Over the next few years, he partnered with French food company BSN (later to become Danone SA) to acquire six companies across Asia, earning him the title of Biscuit King.

The entry into India also included a deal with Coca-Cola for a canceled and much-hyped relaunch in India. In the end, the American fizz giant wanted to participate alone and called off negotiations. One reason may be that Pillai’s ever-growing empire was in jeopardy due to mounting debt. By 1993, his financial situation was dire and he was forced to start selling off parts of his company.

challenger

There he crossed swords with Nusri Wadia, another corporate warrior and survivor of many bloody takeover battles. Pillai’s seemingly unstoppable force met Wadia’s immovable object and the former had to give way.

Through a series of maneuvers, Wadia acquired an equal stake in Britannia as Danone, and both companies ousted Pillai from their boards. Pillai’s claim to control the company was weak because Wadia and Danone controlled 51% of the shares. The sacking has come at a huge cost to Mr Pillai, with his former leader Mr Johnson now demanding a return of the initial funding provided by Mr Pillai.

Cash-strapped and unable to meet his debts, Pillai was taken to court by the Singapore Commercial Authority on multiple charges, including breach of trust, fraud and racking up $17.2 million in debt. But he was too slippery a customer to be easily caught. He fled the country for India on the morning of the verdict. Returning to his hometown, he got an initial reprieve when a court in Kerala granted him bail, but he was subsequently arrested by the CBI from Delhi’s Meridian Hotel in July 1995.

downfall

Pillai has now seen the other side of fame and fortune. His former friends and social acquaintances threw him away like a hot potato. As a disciple of Chandraswami, who wielded great influence in the corridors of power, he was hoping for some help from the self-proclaimed godman. No one came.

Suffering from cirrhosis of the liver, he died in July 1995, just four days after being imprisoned, apparently due to lack of treatment.

His feisty wife Neena Gopika Nehru claimed his death was part of a conspiracy, but in court later she refused to name the alleged co-conspirators.

However, a committee headed by Justice Leila Seth investigated the allegations. Although they found no evidence of a conspiracy, they recommended major reforms to the prison system, which allowed sick people to die without treatment.

Pillai was no angel when it came to risky business practices, as the charges against him proved. But he had fire in his belly and needed lofty talent to succeed in global business. Excessive ambition tended to put him in debt and pit him against too many powerful opponents, but it also proved his undoing.

But for his efforts, he should have been rewarded more than a painful and lonely death in a prison cell. A book written about him by his brother Rajmohan Pillai, A Wasted Death, provides a concise summary of his life.