Yves Blouin

Yves Blouin“I know that a person can die twice. First comes physical death… Being forgotten is the second death,” said screenwriter Yves Bruin, mother of This is stated in the epilogue at the end of his autobiography.

Eve understands this feeling better than anyone.

In the 1950s and 1960s, her mother, the late Andre Blouin, devoted herself to the fight for a free Africa, rallied women in the Democratic Republic of the Congo against colonialism, and became the first Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Patrice.・He rose to become an important advisor to Lumumba. A respected hero of independence.

Although she exchanged ideas with notable revolutionaries such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Sekou Touré of Guinea, and Ahmed Ben Bella of Algeria, her story is little known.

In an attempt to redress this injustice, Blouin’s memoir, My Homeland Africa: The Autobiography of a Black Paschonarian, which has been out of print for decades, is being republished.

In her book, Blouin explains that her longing for decolonization was sparked by a personal tragedy.

She grew up between the Central African Republic (CAR) and Congo-Brazzaville. At the time, these were French colonies called Ubangi Shari and French Congo, respectively.

In the 1940s, her two-year-old son René was hospitalized for malaria in the Central African Republic.

Rene was refused medication because she is mixed race like her mother, and is one-quarter African. A few weeks later, Rene passed away.

“My son’s death politicized me more than anything else could have done,” Blouin wrote in her memoir.

Colonialism, she added, was “no longer a matter of my own evil destiny, but a system of evil whose tentacles extended into every stage of African life.”

Bruin was born in 1921 to a 40-year-old white French father and a 14-year-old black mother from the Central African Republic.

The two met when Buluan’s father passed through her mother’s village to sell his products.

“The story of my father and mother still amazes me, even though it causes me a lot of pain,” Blouin said.

When she was three years old, Blouin’s father sent her to a mixed-race convent run by French nuns in neighboring Congo-Brazzaville.

This was a common practice in French and Belgian African colonies, where thousands of children born to colonialists and African women were sent to orphanages and isolated from the rest of society. It is believed that it was done.

Bruin writes, “Orphanages served as a kind of garbage can for the waste of this black-and-white society, mixed-race children who didn’t fit anywhere.”

Yves Blouin

Yves BlouinBlouann’s experience at the orphanage was extremely negative, she wrote, with children there being whipped, underfed and verbally abused.

But she was stubborn. She ran away from an orphanage at the age of 15 after nuns tried to force her to marry.

Blouin eventually married twice on his own accord. After René’s death, she moved with her second husband to Guinea, a West African country that was also ruled by France.

Guinea was in the midst of a “political storm” at the time, she writes. France promised independence to Guinea, but also required Guineans to hold a referendum on whether to maintain economic, diplomatic, and military ties with France.

The Guinean branch of the pan-African movement RDA called for a “no” vote, saying the country needed complete liberation. In 1958, Blouin joined the campaign and drove around the country addressing rallies.

A year later, Guinea secured independence with a “no” vote, and Guinea RDA leader Sekou Touré became the country’s first president.

By this point, Blouin had begun to have considerable influence in postcolonial Pan-African circles. After Guinea gained independence, she used her influence to advise Barthelemy Boganda, the new president of the Central African Republic, and to avoid a diplomatic spat with Fulbert Helou, leader of Congo-Brazzaville after independence. He wrote that he had persuaded him to withdraw.

But counseling wasn’t the only thing Bruan had to offer this rapidly changing Africa.

At a restaurant in Conakry, the capital of Guinea, she met a group of liberation activists in what would become the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They urged her to help mobilize Congolese women in the fight against Belgian colonial rule.

The Bruins were pulled in two directions. On the other hand, she had three young children, including Eve, to raise. On the other hand, “she had an idealist’s restlessness with a kind of anger at the world as it was,” Eve, now 67, told the BBC.

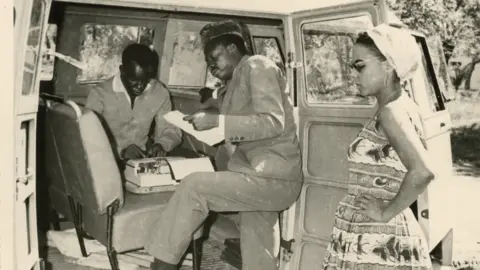

In 1960, with Nkrumah’s encouragement, Andre Blouin flew alone to the Democratic Republic of Congo. She joined prominent men’s liberation activists such as Pierre Murellet and Antoine Gizenga on the streets, campaigning across the country’s 2.4 million square kilometers (906,000 square miles). She painted striking figures traveling through the bush with slicked-back hair, close-fitting dresses, and chic, translucent hues.

Yves Blouin

Yves BlouinIn Cahemba, near the border with Angola, Blouin and his team suspended operations to help Angolan independence fighters who had fled Portuguese colonial authorities build a base.

She addressed the crowd, encouraging them to promote gender equality and independence for Congo. She also had a talent for organization and strategy.

Soon, colonial powers and the international press took notice of Blouin’s work. They accused her of being Nkrumah’s mistress, Sekou Toure’s agent, and “the high-class prostitute of all African heads of state.”

She gained even more attention when she met Lumumba.

In his book, Blouin describes him as a “lithe, elegant” man whose “name was written in letters of gold in the Congolese sky.”

When the country gained independence in 1960, Lumumba became its first prime minister. He was only 34 years old.

Lumumba selected Blouin to be his “chief of protocol” and speechwriter. The two worked so closely together that the press nicknamed them the “Rumamu-Bruins.”

Time magazine described Blouin as a “handsome 41-year-old” whose “steel of will and quick energy make her a valuable political aide.”

However, within just a few days of taking office, a number of disasters befell the Lumam-Blouin team and the newly formed government.

First, the military revolted against white Belgian commanders, sparking violence across the country. Subsequently, Belgium, the United Kingdom, and the United States supported Katanga’s secession. Katanga province is a mineral-rich region in which all three Western countries had interests. Belgian paratroopers swooped into the country, claiming to restore order.

Blouin described the event as a “war of nerves” and that traitors were “organized everywhere.”

Herbert Weiss

Herbert WeissShe wrote that Lumumba was a “true hero of our time,” but admitted that she thought him naive and sometimes too soft.

“It is true that people of sincere faith are often the most cruelly deceived,” she says.

Within seven months of Lumumba taking command, Army Chief of Staff Joseph Mobutu assumed power.

On January 17, Lumumba was shot with tacit support from Belgium. While the United States had previously organized a plot to kill Lumumba, fearing that Lumumba had sympathies with the Soviet Union during the Cold War, Britain may have been complicit.

In his book, Blouin said he was speechless with the shock and sadness caused by Lumumba’s death.

“I have never been left without something to say,” she wrote.

She was forced into exile after Mobutu’s coup and was living in Paris at the time of her murder.

To prevent Blouin from speaking to the international press, authorities kept her family, who had emigrated to Congo, in the country as “hostages.”

The separation was a shock to Blouin, who, as Eve describes, was “very protective” and “very maternal.”

Reflecting on her mother’s personality, Eve added, “You don’t want to antagonize your mother, because even if she has a generous and forgiving heart, she can be quite unstable.”

While Blouin was in exile, soldiers ransacked her family home and brutally beat her mother with a gun, permanently damaging her spine.

Bruin’s family was finally able to join her after months of separation.

They spent a short time in Algeria, where they were offered shelter by the country’s first post-independence president, Ahmed Ben Bella.

They then settled in Paris. Bruin remained involved in Pan-Africanism from afar “in the form of articles and almost daily meetings,” Eve writes in the epilogue of his memoir.

Herbert Weiss

Herbert WeissWhen Blouin began writing her autobiography in the 1970s, she still had great respect for the independence movement to which she had dedicated herself.

She had high praise for Sekou Touré, who at that time had established a one-party state and brutally suppressed freedom of expression.

But Blouin was deeply disappointed that Africa was not as “free” as he had hoped.

“It is not outsiders who are doing the most damage to Africa, but the shattered will of its people and the selfishness of some of our leaders,” she wrote.

She was so sad over the death of her dream that she refused to take medicine to treat the cancer that was ravaging her body.

“It was horrible to watch. I was completely helpless,” Eve said.

Blouin died in Paris on April 9, 1986 at the age of 65. Eve said her mother’s death was met with “grim indifference” from the public.

However, she continues to be an inspiration in some areas. Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, is home to a cultural center named after Blouin that offers educational programs, conferences, and film screenings, all underpinned by a Pan-African spirit.

And through My Country, Africa, Blouin’s extraordinary story is made public for the second time, this time to a world that cares deeply about women’s historical contributions.

New readers will learn about the girl who went from being hidden by the colonial system to fighting for the freedom of millions of black Africans.

My Country, Africa: The Autobiography of a Black Passionarian (published by Verso Books) will be released in the UK on January 7th.

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC