Sign up by email for daily news updates from CleanTechnica. Or follow us on Google News!

Hydrogen wanted a role in aviation date dating back to the mid-20th century, when researchers began investigating its potential as an alternative to traditional jet fuels. In 1957, Lockheed and Boeing engineers investigated hydrogen propulsion as part of a Cold War effort to develop long, durable aircraft at high altitudes. In 1959, the revised Martin B-57 Canberra flew with one engine running on liquid hydrogen. In the late 1980s, the Soviet Union flew the Tupolev TU-155. This is the modified TU-154 airliner for the TU-154, which became the first jet to fly using only liquid hydrogen.

After the Cold War, interest in hydrogen aviation waned as jet fuel remained cheap and dominant. However, growing concerns about climate change and carbon emissions have rekindled research into hydrogen propulsion in the 2000s. Boeing made headlines in 2008 with the first successful flight of a small aircraft fully equipped with hydrogen fuel cells. In the 2010s, European aerospace leaders, including Airbus, culminated in the design of Airbus-equipped aircraft in 2020, a three-hydrogen-powered aircraft design aimed at commercial services, by 2035, to create a long-term solution. He began to seriously explore hydrogen. Zeroavia and universal hydrogen were trying to develop renovations to the local aircraft. Light Electric had hydrogen as one of the possible power sources, along with comparable dead ends in aluminum batteries.

By 2017 I had already evaluated most modes of transport and eliminated hydrogen as an option. At the time, I wasn’t in deep detail in railroads, sea transport or aviation, so I thought that hydrogen might have a role in these modes. I then did my own work and concluded that hydrogen is not playing a role in playing with its own costs and challenges.

As I told anyone who worked on Zeroavia in a recent conversation, in 2017, we evaluated the authentication challenges, storage challenges, aircraft challenges, aircraft balances, cost challenges, or airports during flight challenges. It wasn’t there. Infrastructure challenges. I’ve had it ever since.

After being asked to join the UK academic panel a few years ago, I summarise the key points of the article.

One of the biggest challenges is the low energy density by volume. Hydrogen has a higher energy per kilogram, but it takes up much more space than jet fuel and requires a much larger and heavier tank. This extra bulk increases drag, reduces the efficiency of the aircraft, limiting range and passenger capacity.

Another major obstacle is cryogenic storage. Liquid hydrogen must be kept at -253°C and require a highly insulated tank that adds weight and complexity. Unlike jet fuel that can be stored on aircraft wings, hydrogen requires separate, significantly strengthened tanks, making aircraft design even more difficult.

The lack of infrastructure further complicates hydrogen survival. Airports around the world are built around jet fuel, and the transition to hydrogen requires large investments in production, storage and refueling systems. Due to the costs and logistical challenges of these shifts, large-scale adoption is unlikely to occur in the near future.

Safety is also a concern. Hydrogen is highly flammable and modern containment systems reduce risk, but the aviation industry needs to develop new safety protocols. Additional precautions required for handling and storing hydrogen make implementation more difficult and expensive.

Finally, economics is not summed. Development of new aircraft designs, overhauling airport infrastructure, ensuring safety compliance is extremely expensive. Hydrogen cannot compete as more practical alternatives such as sustainable aviation fuels and battery-electric aircraft emerge.

What works? Well, at first, we were telling everyone that growth in demand, lower than official forecasts from IATA and Boeing, would follow the curve from 1990 to 2019.

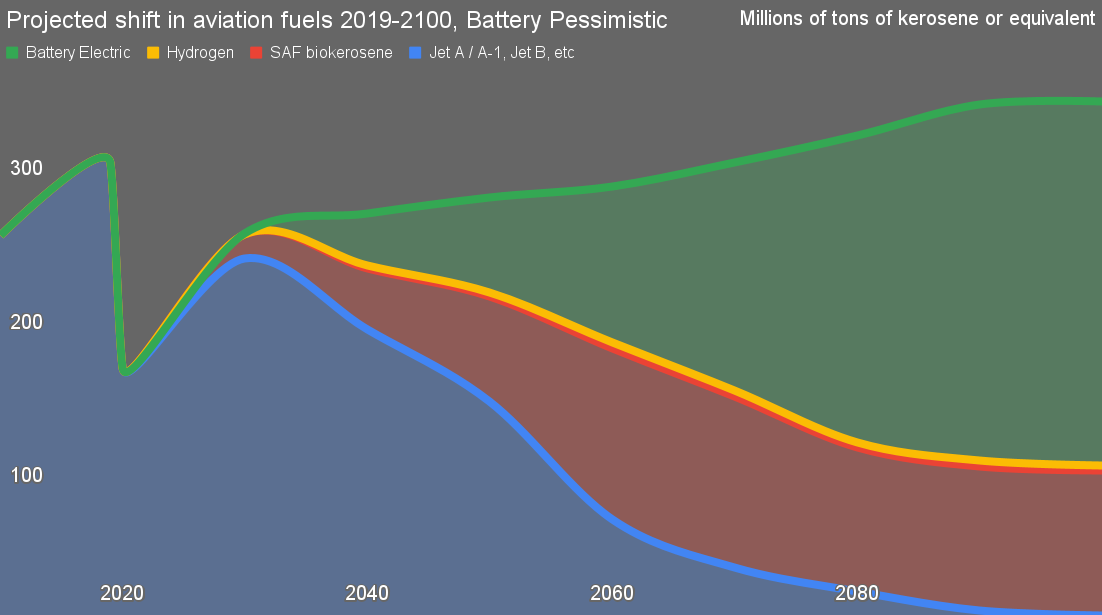

Lightly updated in mid-2024, my projections look at battery electricity, hybrid electricity and SAF biofuels that are far less rosy to growth and provide the energy needed for all aviation. Battery and hybrid electric dominate flights across most continents, with up to 100 passenger turboprops traveling up to 1,000 km of flights. In most cases, hybrid biofuel generators are only needed for repurposing and spare. SAF biofuels are still needed to cross the ocean, but even hybridization, such as auxiliary power units, is now standardized, with things like battery electricity being transferred today. In this context, recent news from the aviation industry has fallen.

One of my predictions for 2025 is that there will be a blood band in hydrogen for the transport segment. At the end of the year, I have to figure out whether I’m right, so I compiled a list of companies in the space where I’m currently 115 years old in total. The table above is the aviation segment, representing 12 companies. I’m sure I missed the couple so please point them out so that you can add them to the list. A high-risk rating means it is likely to be discontinued in next year or two. A low rating – there’s nothing on aviation – means they’re not putting the whole company at risk for their efforts while they lose their money. For integrity, moderate risk means they lose enough money to go out of business altogether.

First outside the space was Light Electric. I released a white paper a few years ago using the aviation powering option and realized that by 2021 batteries and hybrid biofuels would do their job and abandon hydrogen. A simple techno economic analysis for victory, as the company didn’t bother to waste a lot of time and money on hydrogen.

Universal Hydogen, a startup founded in 2020 by former Airbus CTO Paul Eremenko, has eliminated the decarburization of aviation by modifying local aircraft with hydrogen fuel cell powertrains and developing modular hydrogen distribution systems. I was aiming to turn it into carbon. In March 2023, the company successfully flew a hydrogen-powered modified dash 8. Universal hydrogen was stopped operation in June 2024 due to financial challenges. Hydrogen pods were one of the worst ideas I’ve heard recently, so it’s no surprise that they were out of the market early.

Among the majors of Airbus, Boeing, Embler and Comac – China’s major civil airlines – the efforts have been relatively small, but at least they have been significantly promoted by Airbus, but the three conceptual aspects of that are likely It is the highest profile initiative. Now, Airbus has “stops” all its efforts on hydrogen, and after ultimately wasting a lot of engineers’ time, I realized that it was clear from a brief analysis. Many observers tended to suggest that manufacturers were not serious about decarbonisation and that it might be true.

News that Airbus is withdrawing from the hydrogen game came just days after the new destination 2050 roadmap was cut. The roadmap is supported by five major European aviation associations and collectively represents thousands of companies across the sector. European airlines (A4E) represent more than 3,600 aircraft and nearly 2,100 destinations. Airport Council International Europe (ACI Europe) covers more than 600 airports that handle 90% of European air traffic. The Association of Aerospace, Security and Defense Industry (ASD) represents over 4,000 companies, accounting for 98% of the industry’s revenue. Civil Air Navigation Services Organization (CANSO) supports over 90% of the world’s air traffic through air navigation service providers and industry suppliers. Finally, the European Regional Airlines Association (ERA) includes over 50 airlines and around 150 companies involved in regional air transport. It’s basically everyone involved in European aviation, and many of them are global.

The roadmap graphs the pathways for European aviation to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. Originally, hydrogen-powered aircraft were predicted to contribute 20% of emission reductions, but the recent decline has reduced this to just 6%. and recruited. As a result, the plan is currently leaning heavily towards market-based measures to promote sustainable aviation fuels (SAF), operational efficiency, and decarbonization. Boeing Forecast – Passenger traffic factored into emission reduction strategies. Without a doubt, IATA and Boeing hope that the massive growth of developing countries will compensate for limited growth in Europe, but as decarbonization continues to grow Jack ticket prices and fast rails and virtual meetings, I think they think they’re wrong.

A simple prediction for me is that the Air Major Airbus has dropped out and the other three majors are doing R&D with very limited demonstrators, so 6% will drop to 0% over the next few years . The rest of the majors will remove limited efforts and startups will go bankrupt most of this year. That’s a good thing. In fact, hydrogen is a greenhouse gas that is 12-37 times stronger than carbon dioxide for 100 and 20 years, respectively, if indirect, and 1% + hydrogen leaks at every touchpoint in the supply chain.

Aviation hydrogen blood baths are shaped nicely, just like electric vertical takeoff and landing (EVTOL) blood baths. Actual decarbonization efforts such as battery-electric hybrids and SAF biofuels can attract more attention now.

Use your tip for a few dollars a month to support independent CleanTech coverage that helps accelerate CleanTech Revolution! Do you have any tips for CleanTechnica? Want to promote? Want to suggest guests for CleanTech Talk Podcasts? Please contact us here. Sign up to our Daily Newsletter for 15 new CleanTech stories a day. Or, if your daily life is frequent, sign up for one each week. advertisement

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. Please see this policy.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy