America is a massive country, spanning not just geography but generations of shifting ideals, contradictions, and cultural identities. What it means to be American—and by extension, what it means to be patriotic—has never been a single, fixed idea. Patriotism can be found in triumphant stories of heroism, in quiet acts of resilience, in sharp critiques of injustice, and in deep meditations on what this country gets right and what it still struggles with. Cinema has long reflected these tensions, offering portraits of American life that range from inspiring to unsettling, but always deeply engaged with the idea of this nation and its people.

Each of the films on this list, produced and made in America by American filmmakers, explores a facet of patriotism in its own way. Some celebrate the country’s highest ideals, while others challenge its failures—yet all embody a belief in the power of storytelling to grapple with what America is and what it could be.

From the high-flying bravado of Top Gun to the quiet, realism of Wendy and Lucy, these films capture the spirit of a country that is constantly in conversation with itself. Whether through historical reflection, personal struggle, or institutional critique, they remind us that patriotism is not just about pride— it’s also about the American ideals of reckoning and the pursuit of something better.

15

‘The Florida Project’ (2017)

Few films capture modern American poverty with the immediacy and warmth of The Florida Project. Filmed on location in Kissimmee, Florida, just outside the gates of Disney World, the film takes place in a decaying roadside motel painted in the kind of pastel optimism that only deepens its tragedy. At the center is six-year-old Moonee (Brooklynn Prince), a precocious, wild child who roams the strip malls and abandoned lots with her equally mischievous friends. Her mother Halley (Bria Vinaite), young and barely scraping by, hustles in ways both legal and illegal to keep a roof over their heads. Meanwhile, Bobby (Willem Dafoe), the gruff but big-hearted motel manager, watches over them with quiet concern. The setting—so close to Disney’s manufactured perfection yet miles away from its promise—turns the film into a bittersweet fable of the real American Dream: one of survival, improvisation, and small, stolen joys.

The American Dream, Seen From the Parking Lot of a Budget Motel

What could be more American than The Florida Project? It is about making something out of nothing, about defying the odds while the system looks away. Moonee and her mother exist in the shadow of a country that was built on the idea of endless possibility, yet their lives are defined by the exact opposite. But rather than sinking into despair, Sean Baker finds magic in the struggle. This is the kind of patriotism rarely shown on screen: the patriotism of the invisible, of those who find ways to live, love, and dream despite being locked out of the fantasy. If America is ever going to be the place it claims to be, it has to look at films like The Florida Project and see its own reflection—not just in the magic, but in the pain.

14

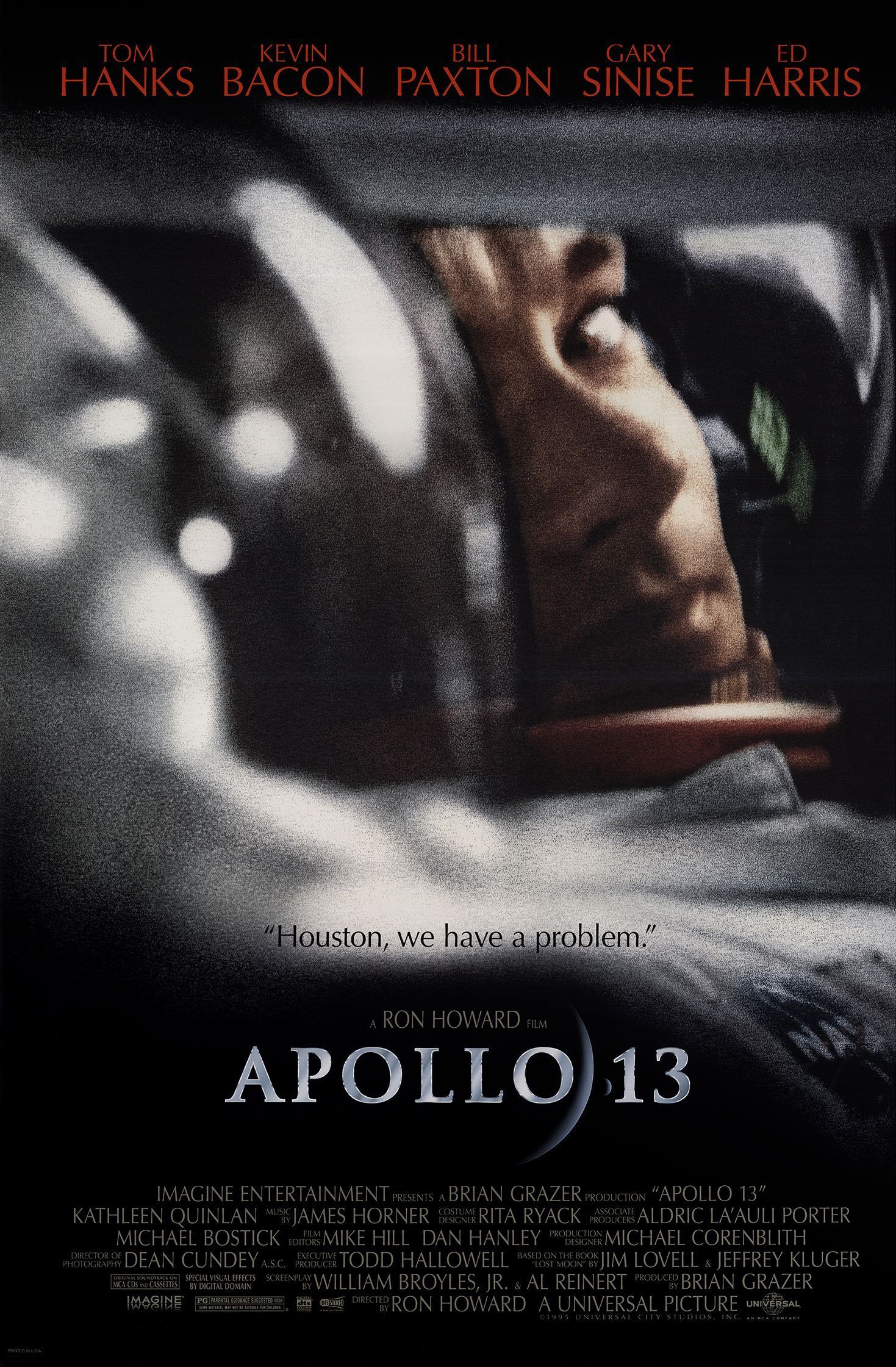

‘Apollo 13’ (1995)

Apollo 13

Release Date

June 30, 1995

Runtime

140 Minutes

Writers

Jim Lovell, Jeffrey Kluger, William Broyles Jr.

Filmed in Houston, Texas, and Cape Canaveral, Florida, Apollo 13 reconstructs one of America’s most famous near-disasters with all the precision and grandiosity of a space-bound procedural. The film follows the ill-fated 1970 Apollo 13 mission, with Tom Hanks as Jim Lovell, Kevin Bacon as Jack Swigert, and Bill Paxton as Fred Haise, three astronauts forced into a desperate fight for survival when an onboard explosion cripples their spacecraft. Down in Houston, NASA’s Mission Control—led by Gene Kranz (Ed Harris) and his now-iconic “Failure is not an option” mantra—races against time to bring them home. The film’s claustrophobic, meticulously crafted visuals pull the audience into the spacecraft itself, making the vastness of space feel even more terrifying.

Failure Is Not an Option, and Other American Myths

If Apollo 13 feels like a classic piece of American myth-making, it’s because it is—but it’s one that earns its place. Unlike many flag-waving hero narratives, it doesn’t center on individual glory but on collective ingenuity, on the uniquely American belief that innovation and perseverance can solve anything. There is no villain here, no enemy to defeat, only the vast indifference of space and the fragile brilliance of human engineering. What makes Apollo 13 endure is its celebration of the very thing that built America in the first place: the refusal to quit, the ingenuity to make something out of nothing, the sheer will to survive. It’s a film about problem-solving as patriotism, about the belief that in a country where the impossible happens all the time, bringing three men home from the edge of oblivion is simply one more challenge to overcome.

13

‘The Social Network’ (2010)

There’s something almost Biblical about the way The Social Network unspools—the story of a nerd scorned, a digital dynasty born out of betrayal, ambition, and the kind of raw, capitalistic hunger that America has always mythologized. The film chronicles the meteoric rise of Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg), a Harvard undergrad who builds the social media giant Facebook while alienating his best friend Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield), facing legal threats from the Winklevoss twins (Armie Hammer), and getting seduced by the snake-oil charisma of Sean Parker (Justin Timberlake). Filmed primarily in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with additional shooting in Los Angeles and Baltimore, the film immerses itself in the Ivy League elitism and startup hustle that defined Zuckerberg’s early years. While set within Harvard’s cloistered halls, the film sprawls across America’s digital landscape, touching the highest levels of wealth, power, and litigation.

The Algorithm of American Patriotism

If America is about anything, it’s about reinvention. The Social Network is a film about building something out of nothing—about how ambition, ego, and obsession can sculpt a new world overnight. It’s also about America’s most enduring contradiction: the belief that success must come at any cost. Zuckerberg embodies the tech-era frontiersman, not with a rifle and a horse, but with code and ruthless efficiency. This is modern patriotism in its rawest, most conflicted form: innovation as a blood sport, progress as a solitary pursuit. Watching The Social Network now, in a world where Facebook has metastasized into something more monstrous than anyone could have imagined in 2010, makes it an even more essential American text—one that asks, without sentimentality, whether power can exist without corruption.

12

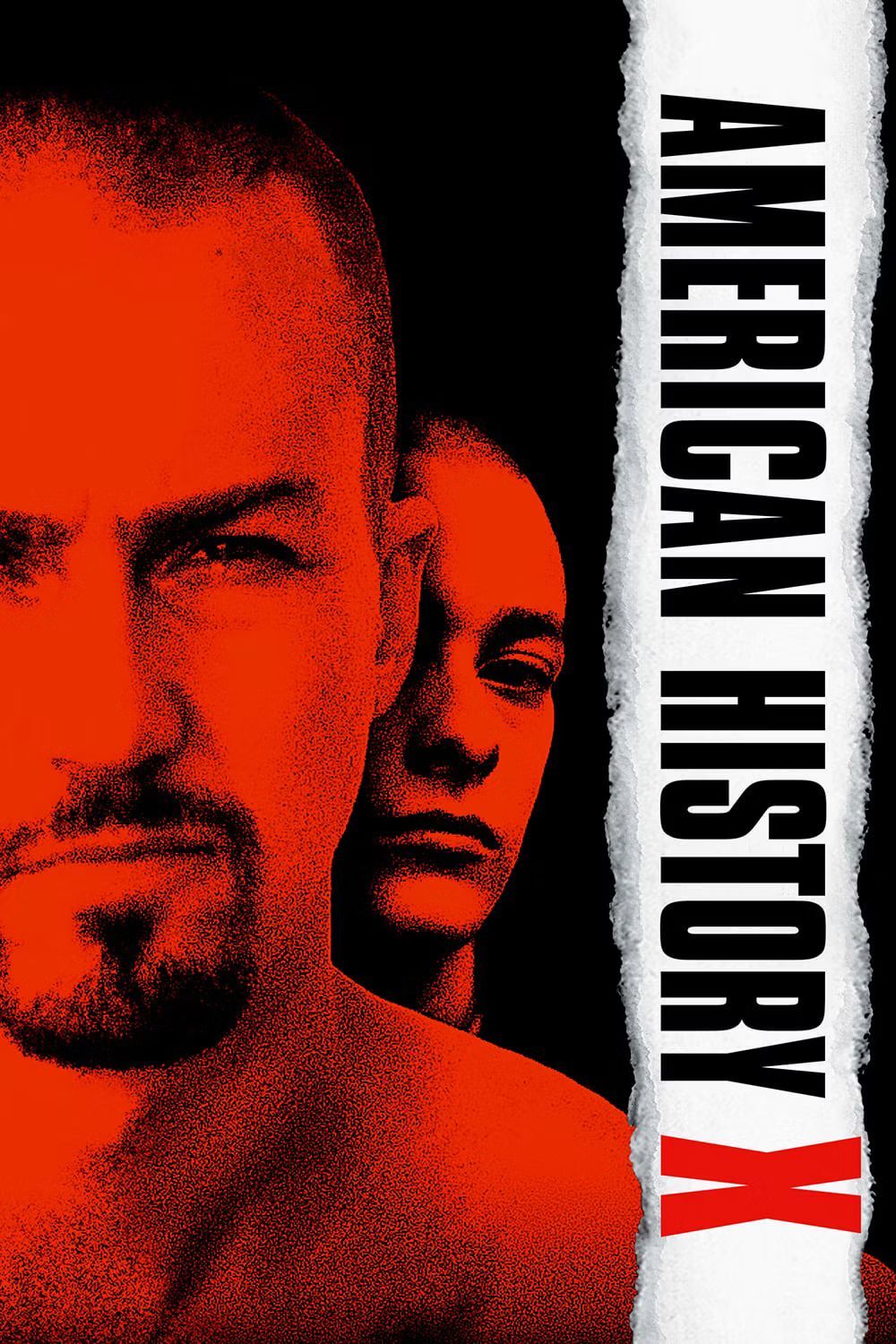

‘American History X’ (1998)

American History X

Release Date

November 20, 1998

Runtime

119 Minutes

Writers

David McKenna

Shot in the sun-bleached sprawl of Los Angeles, American History X is a film about the dark underbelly of American ideology, a brutal dissection of how hate festers in the cracks of the American Dream. Edward Norton stars as Derek Vinyard, a charismatic, violently racist skinhead whose worldview is dismantled in prison after a series of harrowing experiences. His younger brother Danny (Edward Furlong) idolizes him, soaking in the rhetoric of white supremacy until he, too, is caught in the cycle. Venice Beach, with its juxtaposition of sun-drenched paradise and urban decay, serves as the perfect microcosm of America itself—a place of opportunity and destruction, where ideology is fought over as viciously as territory. Kaye’s stark cinematography, especially in the film’s black-and-white flashbacks, makes every moment feel both deeply personal and eerily mythic.

The Battle for America’s Soul, Set in the Streets of Venice Beach

Patriotism is often mistaken for blind loyalty, but American History X argues that true patriotism means confronting the worst parts of the nation and demanding better. It doesn’t flinch in showing how deep racism runs in American identity—how it is learned, weaponized, and, in rare cases, unlearned. Derek’s transformation is not a redemption arc in the Hollywood sense; it is jagged, incomplete, and devastating. The film is a warning, a gut-punch reminder that hate is not born but built, and that America’s biggest battle has never been external—it has always been the war within itself. Watching American History X is an exercise in discomfort, but it is necessary, because to love a country is to want it to heal.

Related

Anora Continues a Familiar Sean Baker Filmmaking Trend

Sean Baker’s Anora seems set to further explore the lives of its characters in positive and unflinching ways.

11

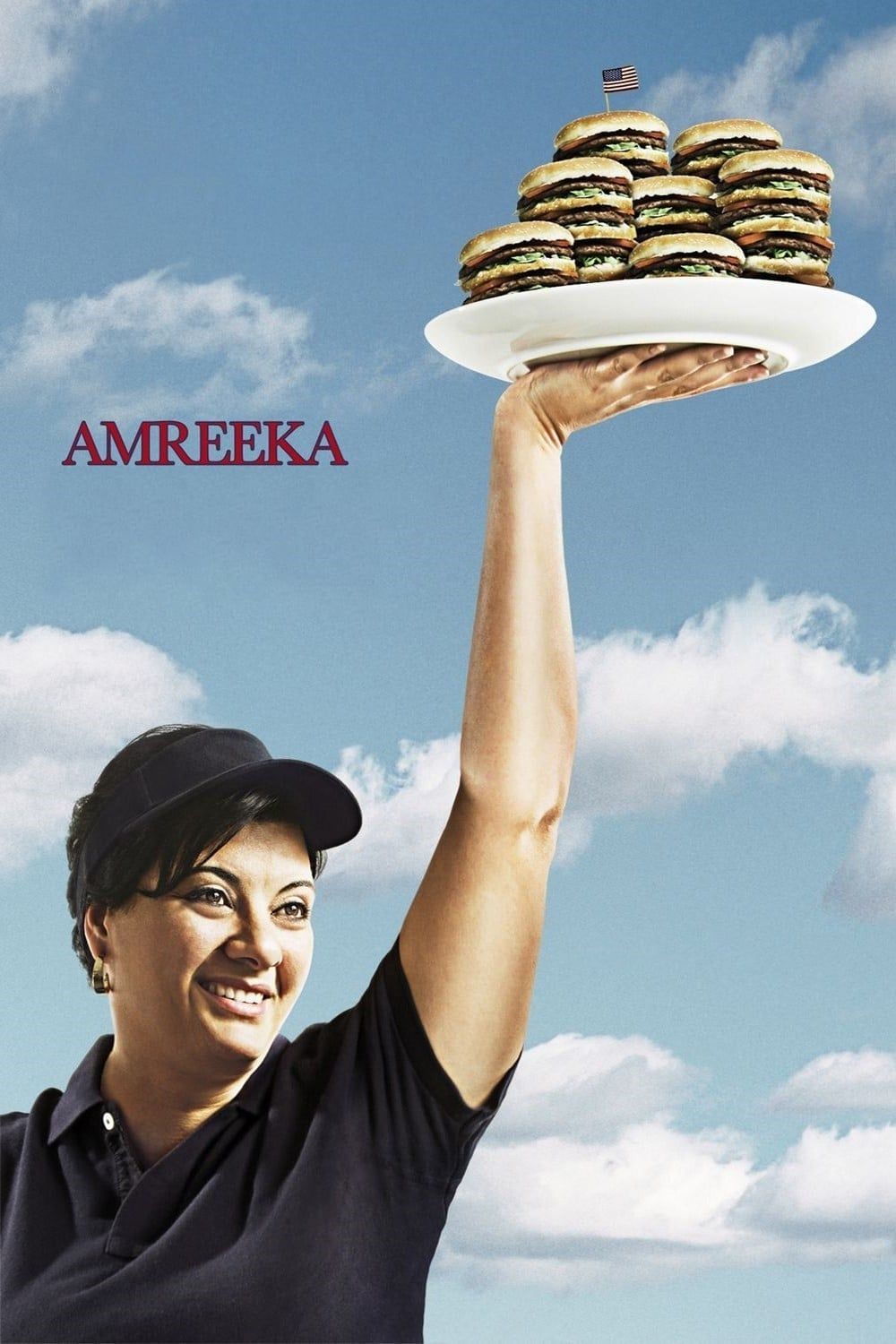

‘Amreeka’ (2009)

Amreeka

Release Date

June 17, 2009

Runtime

96

Director

Cherien Dabis

Writers

Cherien Dabis

Filmed in the small-town landscapes of Illinois and Manitoba (standing in for America’s Midwest), Amreeka tells a story that is at once deeply personal and profoundly American. Muna (Nisreen Faour), a Palestinian single mother, moves to the United States with her teenage son Fadi (Melkar Muallem) in search of a better life—only to find herself caught between post-9/11 xenophobia and the crushing reality that the American Dream is mostly a myth. The film follows her struggles to find work (she goes from banking professional to fast-food worker overnight), navigate cultural clashes, and keep her son from losing himself in the pressure to assimilate. The setting—Middle America, with its strip malls, fluorescent-lit diners, and sterile suburban streets—becomes a quiet but potent backdrop for a story about the contradictions of American belonging.

The Immigrant’s Journey, Between Hope and Disillusionment

The most American thing about Amreeka is Muna herself. She arrives with optimism, fueled by the same belief that has propelled immigrants for generations—that this country, for all its flaws, might still offer something better. And yet, the film does not turn her struggle into melodrama or tragedy; instead, it finds humor and resilience in her day-to-day survival. Dabis’ film challenges the sanitized narratives of the immigrant experience, making room for the messy, unglamorous reality of starting over in a country that often resists those who need it most. But Amreeka is patriotic in the truest sense: it believes that America can be better, not because it already is, but because its people—immigrants, outsiders, dreamers—keep pushing it forward

10

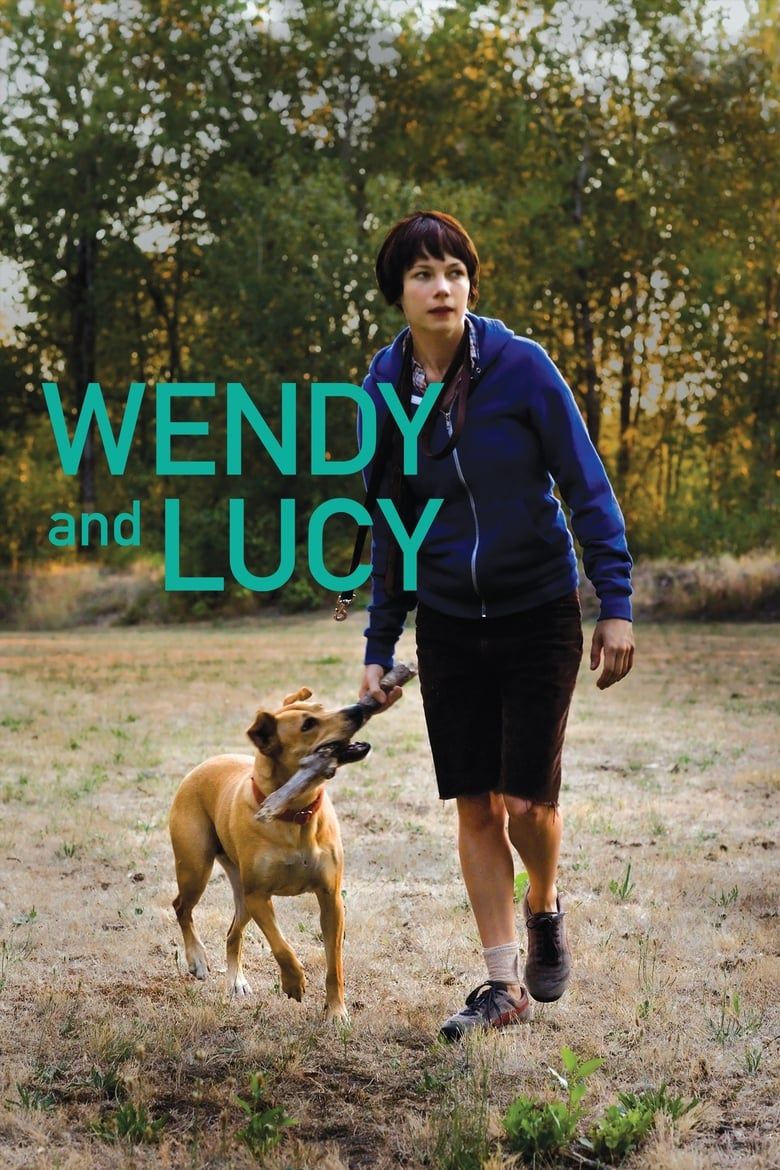

‘Wendy and Lucy’ (2008)

Wendy and Lucy

Release Date

December 10, 2008

Runtime

81 minutes

Writers

Jonathan Raymond

Producers

Joshua Blum, Larry Fessenden, Phil Morrison, Todd Haynes, Anish Savjani, Neil Kopp

Wally Dalton

Security Guard

Shot in the quiet corners of Portland, Oregon, Wendy and Lucy is a road movie in which the road simply runs out. Wendy (Michelle Williams) is on her way to Alaska, chasing the kind of fresh start that only exists in theory, when her car breaks down and her dog, Lucy, disappears. Stranded and nearly out of money, she becomes stuck in a cycle of small, compounding misfortunes—losing a pet, getting caught shoplifting for food, sleeping in her car, being treated as an inconvenience by a country that values productivity over people. The landscapes Reichardt captures are not the vast, romanticized America of classic cinema, but the America of gas stations, big-box stores, empty parking lots, and the vague hostility of anywhere you don’t belong.

Patriotism in the Act of Surviving

Wendy is nobody, which is exactly why Wendy and Lucy is so necessary. It’s a story of a person slipping through the cracks, of a life that doesn’t have the safety net we pretend exists. If patriotism is about valuing the people who make up a nation, then Wendy’s struggle is an indictment of what happens when that promise fails. Kelly Reichardt’s direction is stripped of sentimentality, but that makes it all the more devastating—this is not a tragedy; it is simply life. But in its small, heartbreaking way, Wendy and Lucy is also about resilience, about finding kindness in strangers, about the vastness of America not as a land of opportunity, but as a place where people keep moving, keep trying, because what else is there to do?

9

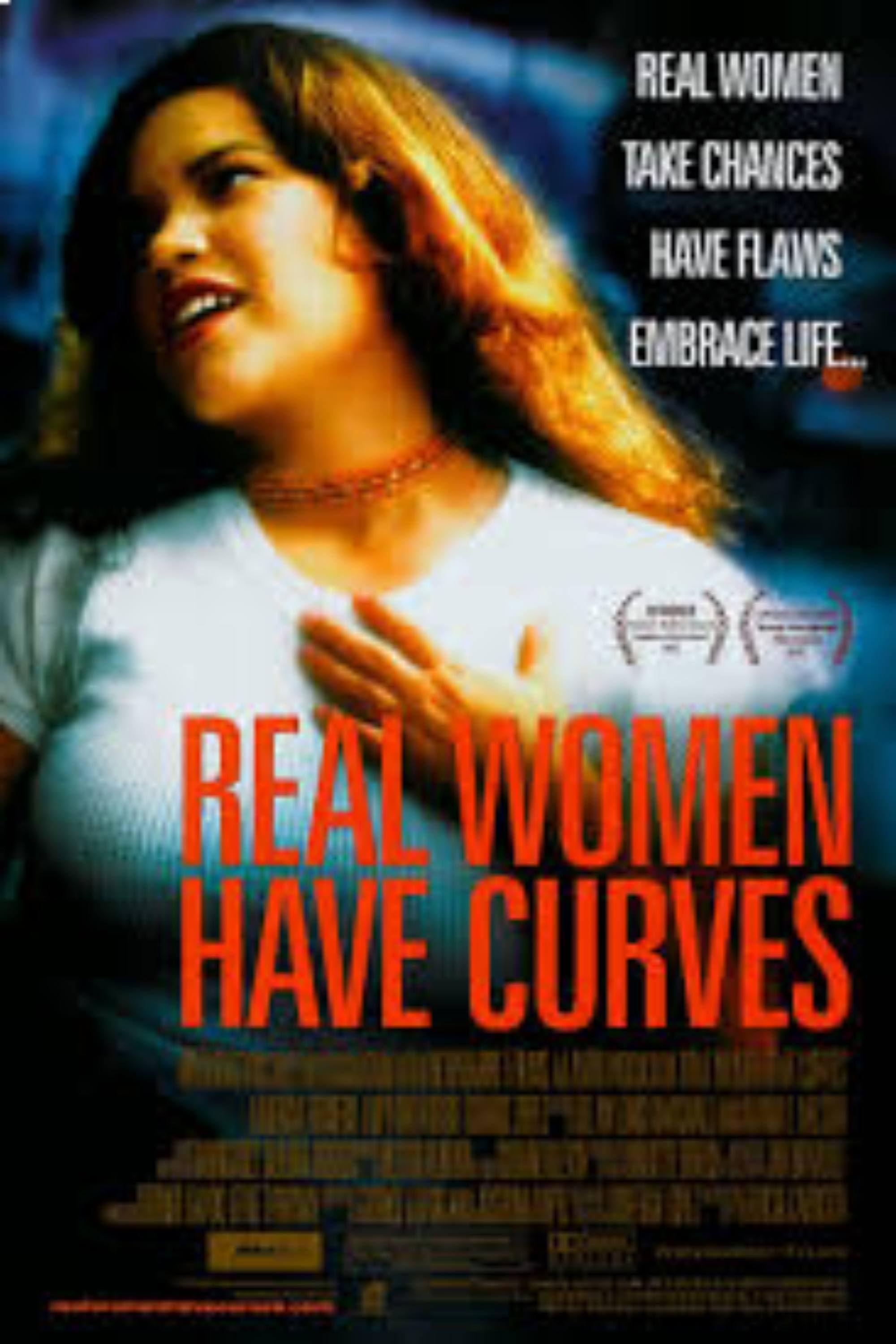

‘Real Women Have Curves’ (2002)

Real Women Have Curves

Release Date

November 8, 2002

Director

Patricia Cardoso

Writers

Josefina Lopez, George LaVoo

Filmed in Los Angeles’ Boyle Heights neighborhood, Real Women Have Curves is both a love letter to the immigrant working-class experience and a deeply feminist coming-of-age story. Ana (America Ferrera, in her breakthrough role) is a Mexican-American teenager caught between two versions of herself: the dutiful daughter expected to work at her family’s sweatshop and the ambitious young woman eager to chase her academic future. Her mother (Lupe Ontiveros) is her biggest roadblock, clinging to old-world expectations, while Ana finds unexpected solidarity among the other women at the factory. The film’s setting—sprawling LA, where the American Dream is manufactured but rarely guaranteed—mirrors Ana’s own fight to carve out a space for herself in a country that often renders young, working-class Latina women invisible.

Coming of Age in the Gaps Between Generations

There’s something profoundly American about Ana’s defiance—about her refusal to be small, to shrink herself down to meet expectations. Real Women Have Curves isn’t just about body image or cultural clashes; it’s about self-determination, about demanding more from a country that often asks its immigrant daughters to settle for less. Ana doesn’t reject her roots—she challenges the idea that honoring them has to mean limiting herself.

The film has drawn comparisons to Lady Bird (2017) for its deeply personal exploration of mother-daughter conflict, economic struggle, and the tension between staying home and pursuing dreams elsewhere. Yet while Lady Bird was celebrated for its universality, Real Women Have Curves has often been overlooked in the mainstream, despite covering the same emotional terrain with just as much honesty and wit. Patricia Cardoso’s film is joyful, defiant, and quietly radical in the way it insists that America belongs just as much to women like Ana as it does to anyone else. True patriotism, Real Women Have Curves argues, isn’t about assimilation—it’s about taking up space on your own terms.

Related

Most Underrated Coming of Age Movies

From The Way Way Back to Waves, these are some of the most heartfelt and underrated coming of age movies everyone needs to see.

8

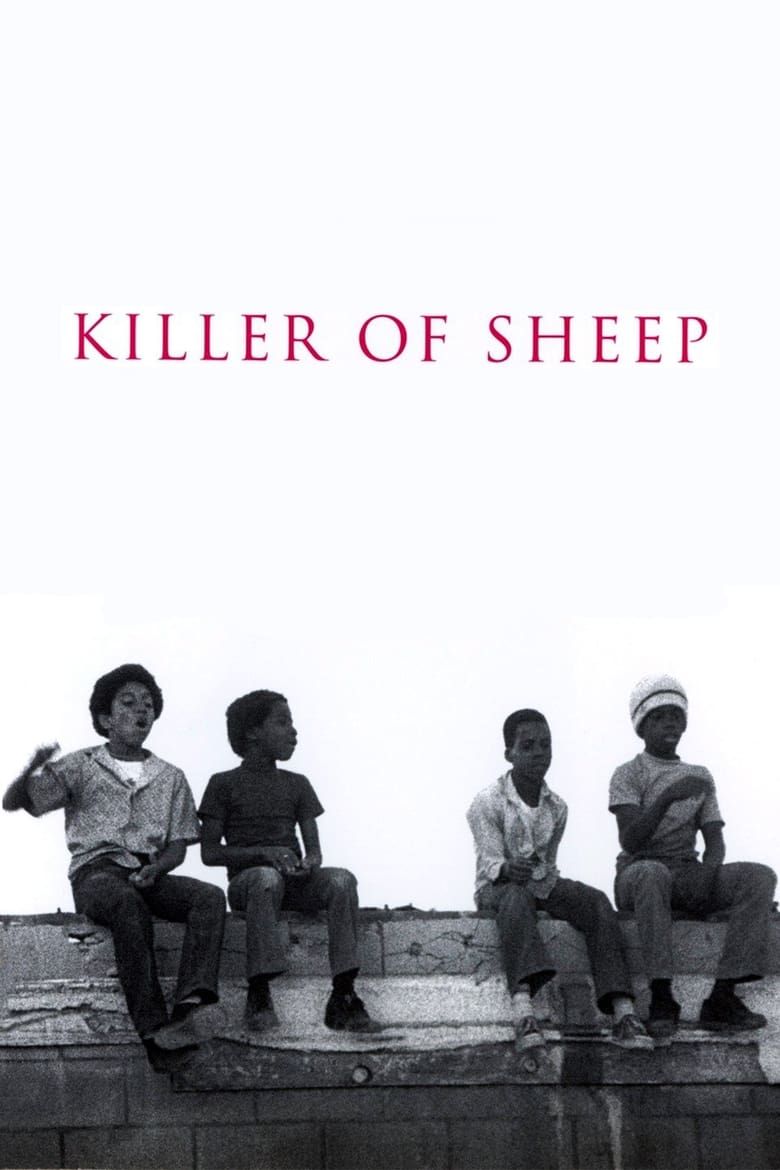

‘Killer of Sheep’ (1978)

Killer of Sheep

Release Date

November 14, 1978

Runtime

80 minutes

Director

Charles Burnett

Angela Burnett

Stan’s Daughter

Filmed in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles with a cast of non-professional actors, Killer of Sheep is an unfiltered, lyrical portrait of working-class Black life in America. At its center is Stan (Henry G. Sanders), a slaughterhouse worker slowly worn down by exhaustion, poverty, and the quiet weight of being a Black man in a country that seems indifferent to his survival. The film unfolds in a series of vignettes rather than a traditional narrative—kids playing in empty lots, couples dancing in dimly lit rooms, the mechanical repetition of work and home—each moment a snapshot of joy, struggle, and resilience. Burnett shot the film guerrilla-style over several years, capturing Watts in the wake of the 1965 riots, but rather than focusing on explicit political upheaval, Killer of Sheep lingers on the everyday realities of life in America’s margins.

The Other Side of the American Dream

If the American Dream was meant to be universal, then Killer of Sheep is proof of its limitations. And yet, Charles Burnett’s film is not an indictment—it is an act of preservation, a record of lives rarely centered in cinematic history. The film doesn’t try to impose an easy narrative or force hope where there is none. Instead, it finds its patriotism in witnessing, in showing a part of America often ignored, in capturing a beauty that is rarely acknowledged. This is what makes Killer of Sheep essential: it expands the definition of what American stories look like, whose lives matter in the national consciousness, and what history is worth remembering.

7

‘Leave No Trace’ (2018)

Filmed deep in the forests of Oregon, Leave No Trace follows a father and daughter living off the grid, surviving in the woods until they are discovered by authorities and forced to reenter society. Will (Ben Foster), a veteran suffering from PTSD, has chosen to raise his daughter Tom (Thomasin McKenzie) in a state of quiet, self-imposed exile. But Tom, on the brink of adolescence, begins to question their nomadic existence. Granik’s film, like Winter’s Bone before it, strips away the romanticism of rugged American individualism, instead exposing its cost: paranoia, isolation, and a relentless fight to stay invisible. The landscapes—lush, endless forests, small rural homes, quiet campsites—reflect a version of America where freedom and survival are constantly at odds.

An American Wilderness, Not Meant for Everyone

In a country built on the myth of self-reliance, Leave No Trace asks what happens when that very instinct becomes an act of survival rather than empowerment. Will’s existence is an extreme form of American independence, but it’s also a tragedy—one shaped by a country that cycles its soldiers through war and then leaves them to fend for themselves. Yet the film’s patriotism is not in its critique alone; it is in Tom’s growing desire for connection, her realization that survival isn’t just about autonomy but about belonging. Debra Granik offers an alternative to the rugged American loner archetype—one where healing is not found in isolation, but in the willingness to be part of something bigger. It’s no surprise that Leave No Trace resonated beyond film circles, earning a place on former President Barack Obama’s list of favorite films of 2018, a testament to its quiet but powerful reflection on the American condition.

Related

Michael B. Jordan & Ryan Coogler Tease Their Vampire Horror Movie With New Footage

Ryan Coogler and Michael B. Jordan are finally reuniting for a horror movie based on an original concept.

6

‘Fruitvale Station’ (2013)

Shot on location in the Bay Area, Fruitvale Station tells the real-life story of Oscar Grant (Michael B. Jordan), a 22-year-old Black man killed by police at a train station on New Year’s Eve 2008. The film, stripped of courtroom drama or political grandstanding, follows Oscar through the last day of his life, painting a deeply intimate portrait of a man trying—like so many others—to build something better for himself and his family. He drops his daughter off at school, argues with his girlfriend, considers selling weed to pay rent, helps a stranger at the grocery store. Ryan Coogler refuses to turn Oscar into a martyr or a statistic; instead, he makes him undeniably, painfully human.

The American Tragedy That Keeps Happening

There is no neat resolution in Fruitvale Station because there is no resolution in the reality of police violence. But Coogler’s film is essential because it refuses to let Oscar Grant’s death be reduced to just another news cycle. It demands that America reckon with itself, with the ways in which its justice system fails, with the fact that patriotism—real patriotism—requires acknowledging the ways the country continues to betray its own people. Watching Fruitvale Station is an act of remembering, of refusing to let history erase the names of those lost to a system that was never designed to protect them. It is a film that mourns, but it is also a film that insists on seeing, on refusing to look away. And that, in itself, is an American responsibility.

5

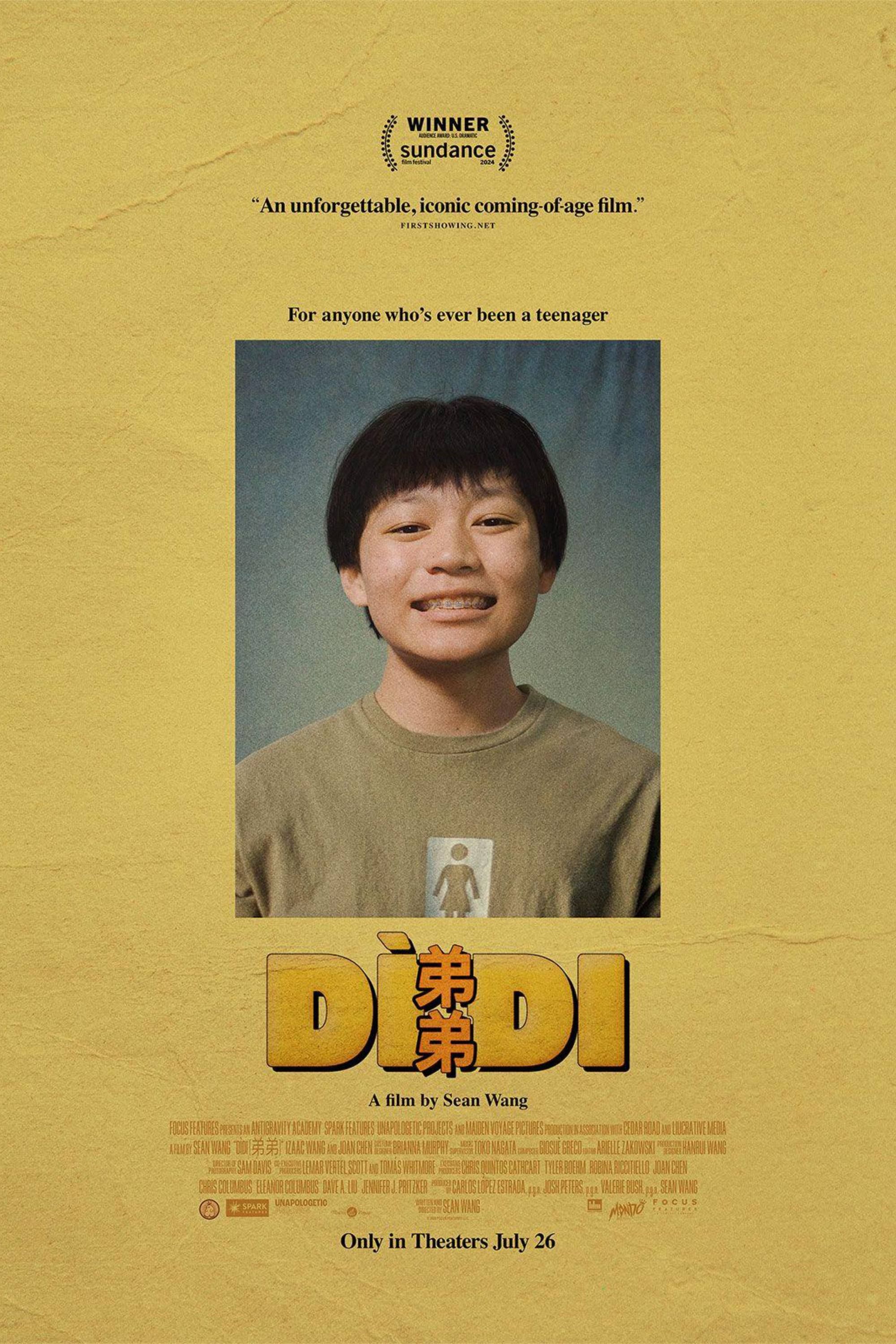

‘Dìdi (弟弟)’ (2024)

Dìdi

Release Date

August 16, 2024

Runtime

94 Minutes

Director

Sean Wang

Writers

Sean Wang

Filmed in the suburban landscapes of Fremont, California, Dìdi (弟弟) is a coming-of-age story that unfolds during the summer of 2008, capturing the last gasps of adolescence for a Taiwanese American teen. Chris (Izaac Wang) is 13, awkward, eager, and constantly navigating the push and pull of his identity—his American upbringing, his immigrant parents, his skateboarding crew, his crushes, his own uncertain sense of belonging. The film, infused with the hazy nostalgia of camcorder home videos and period-specific references (AIM chatrooms, early YouTube culture), unfolds in that liminal space between childhood and growing up, between tradition and assimilation, between who you are and who you want to be.

The 4th of July, Through the Eyes of a First-Generation Kid

Unlike the grand, sweeping narratives often associated with patriotism, Dìdi (弟弟) finds its Americanness in the details: a 4th of July barbecue, a suburban skate park, the awkward bilingual exchanges between Chris and his mother. The film captures the immigrant experience with warmth and honesty, not as a struggle to fit in, but as a reality lived in small, everyday negotiations. What does it mean to grow up American when your roots are elsewhere? How do you carve out an identity in a country that both embraces and alienates you? Dìdi (弟弟) doesn’t offer easy answers, but in its specificity, it finds something universal. This is the kind of patriotism that doesn’t need a grand declaration—it’s in the quiet moments, in the messy in-between spaces, in the simple fact of making a life in a country that is still figuring itself out.

4

‘Songs My Brothers Taught Me’ (2015)

Songs My Brothers Taught Me

Release Date

September 9, 2015

Runtime

98 minutes

Director

Chloé Zhao

Producers

Andrew Fierberg, Forest Whitaker, Nina Yang Bongiovi, Angela C. Lee, Mollye Asher, Michael Y. Chow

Jashaun St. John

Jashaun Winters

John Reddy

Johnny Winters

Irene Bedard

Lisa Winters

Eléonore Hendricks

Angie Britt

Filmed entirely on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, Songs My Brothers Taught Me is a deeply intimate portrait of Native American life, focusing on the relationship between a teenage brother and sister facing the pull between staying and leaving. Johnny (John Reddy) wants to escape the reservation’s economic despair, while his younger sister Jashaun (Jashaun St. John) sees beauty and strength in the home that he is desperate to abandon. Chloe Zhao, working with non-professional actors, captures the everyday rhythms of Pine Ridge—the rodeos, the fireside conversations, the silent weight of history that lingers over the land. The film avoids the usual Hollywood narratives of Native suffering, instead painting a picture of life as it is lived: complicated, joyful, heartbreaking, and endlessly resilient.

An America That’s Always Forgotten

To watch Songs My Brothers Taught Me is to see an America rarely shown on screen—one that exists beyond the borders of mainstream consciousness, yet is more fundamentally American than any of the glossy, sanitized versions we are used to. Zhao does not frame Pine Ridge as a place to be pitied or romanticized; instead, it offers a raw, deeply felt portrayal of what it means to survive in a country that was built on the erasure of Indigenous people. But survival is its own form of resistance, and in Jashaun’s unwavering belief in her home, in the quiet ways her community persists, Songs My Brothers Taught Me finds a patriotism that does not seek approval, only acknowledgment. It is a film that does not beg America to see itself—it simply holds up a mirror and waits.

3

‘American Honey’ (2016)

American Honey

Release Date

September 30, 2016

Runtime

163 Minutes

Director

Andrea Arnold

Producers

Trudie Styler, Celine Rattray, Jay Van Hoy, Lars Knudsen, Thomas Benski, Lucas Ochoa, Rose Garnett, Charlotte Ubben, Pouya Shahbazian, Hardy Justice, Marisa Clifford, Melissa Hook

Shot in real, unglamorous corners of the American Midwest and South, American Honey follows Star (Sasha Lane), a teenager who joins a traveling sales crew of lost kids, drifting from town to town selling magazine subscriptions and chasing something that looks like freedom. The film, shot in Arnold’s signature documentary-like style, is a hypnotic road trip through forgotten America: gas stations, strip malls, motels, empty highways, the detritus of a country where the American Dream has already packed up and left. Star, along with crew leader Jake (Shia LaBeouf) and a van full of restless misfits, exists in a liminal space—always moving, always searching, always running toward an illusion of something better.

The Road to Nowhere and Everywhere

Few films capture the aimless, reckless energy of young America like American Honey. These kids, abandoned by the system and overlooked by society, are still chasing something—an adventure, a connection, a sense of purpose, even if they don’t know where they’re going. If the classic road movie was about self-discovery, American Honey is about the impossibility of finding yourself in a country that barely acknowledges your existence.

And yet, what makes American Honey so uniquely compelling is the fact that its director, Andrea Arnold, isn’t American. A British filmmaker, Arnold approaches the American mythos from the outside looking in, stripping away sentimentality to reveal something rawer, more alien, but also more deeply truthful. Sometimes, it takes an outsider’s gaze to see a country clearly—to capture its vastness, its contradictions, its broken dreams, and the restless people still moving through them. And yet, in its sprawling, sun-drenched chaos, the film pulses with a strange, aching patriotism—not the kind you find in national anthems or Fourth of July parades, but the kind that lives in movement, in music blasting from car windows, in the belief that maybe, just maybe, there’s something worth searching for.

2

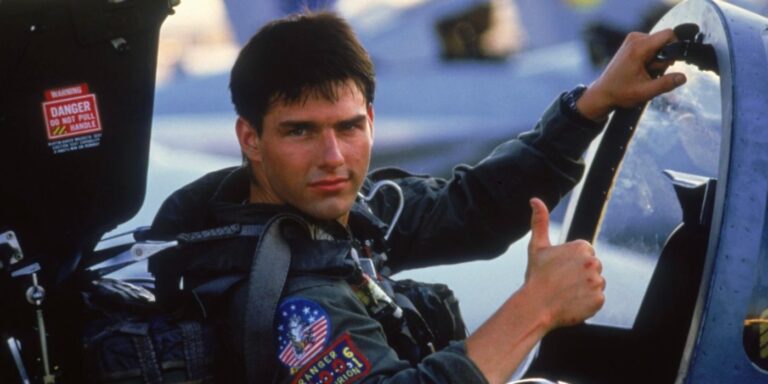

‘Top Gun’ (1986)

Top Gun

Release Date

May 16, 1986

Runtime

110 minutes

Filmed on real U.S. military bases in California and Nevada, Top Gun is pure, high-octane American spectacle—a movie so drenched in sun, sweat, and bravado that it practically plays like a Navy recruitment ad. Pete “Maverick” Mitchell (Tom Cruise) is a hotshot fighter pilot with a need for speed, trying to prove himself at the elite Top Gun naval aviation school. His rival, Iceman (Val Kilmer), represents discipline and control, while Maverick, fueled by ego and the ghosts of his past, is all instinct and recklessness. The film’s iconic aerial dogfights, set against golden-hour skies, are nothing short of hypnotic, turning the F-14 Tomcat into a symbol of both American power and individual exceptionalism.

The Sky Is the Limit, Patriotism as Spectacle

If Top Gun is patriotic, it’s the kind of patriotism that runs on adrenaline and anthems—the kind that makes you want to throw on aviators and ride a motorcycle down an empty runway. And yet, beneath the slick action and iconic volleyball sequences, the film is also about the cost of that American bravado. Maverick’s arc is one of myth-making and self-destruction, of heroism and its inherent loneliness. Top Gun is as much about the way America sees itself as it is about military might—it’s about confidence, about pushing limits, about being the best even when no one asks you to be. It’s a movie that glorifies the American spirit, but also hints at its fragility, its need to constantly prove itself. If there’s a more American contradiction than that, it’s hard to find.

1

‘Mr. Smith Goes to Washington’ (1939)

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington

Release Date

October 9, 1939

Runtime

129 Minutes

Writers

Sidney Buchman, Lewis R. Foster, Myles Connolly

Filmed on Hollywood soundstages meticulously designed to replicate the U.S. Capitol, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington is the ultimate civics lesson wrapped in a political fairy tale. Jimmy Stewart plays Jefferson Smith, a naïve, idealistic nobody who gets appointed to the U.S. Senate, only to discover that the system is rotten to its core. What follows is one of the most famous speeches in cinematic history: a filibuster that turns into a last-stand defense of American democracy, as Smith fights against corruption with nothing but sheer belief in the ideals the country was supposedly built on. The film’s Washington, D.C., setting—though a recreation—feels as grand and imposing as the institutions it critiques, a monument to both democracy’s promise and its hypocrisies.

Patriotism as a Fight, Not a Given

Capra’s film, though sentimental, is not naïve—it recognizes that power is rarely in the hands of those who deserve it. But its brilliance lies in its refusal to surrender to cynicism. Mr. Smith is not just fighting for himself; he’s fighting for the idea that democracy is only as strong as those willing to defend it. The film’s patriotism is not about blind loyalty—it is about the belief that America is worth holding accountable. Watching Mr. Smith Goes to Washington today, in an era of deep political disillusionment, feels almost radical. It is a reminder that patriotism is not found in waving flags or empty slogans; it is found in the messy, exhausting, necessary work of making a country live up to its own ideals.