The ISS’s orbit is slowly decaying. Although it may seem like a permanent fixture in the sky, the orbiting space laboratory is only about 400 km above the planet. There may not be much atmosphere at that altitude. However, some are still present, and interacting with them will gradually slow the station’s orbital speed, reduce its orbit, and eventually pull it back toward Earth. That is, if you do nothing to stop it. Over the station’s 25-year lifespan, hundreds of tons of hydrazine rocket fuel have been delivered to the station to prevent orbit collapse due to rocket propulsion. But what if there was a better way, one that was self-powered, cheap, and didn’t require regular refueling?

A new paper by Giovanni Annese, a PhD student at the University of Padua, and his team focuses on such concepts. It uses a new idea called bare photovoltaic tether (BPT). It is based on the old idea of an electrodynamic tether (EDT), but has several benefits by adding solar panels along its entire length.

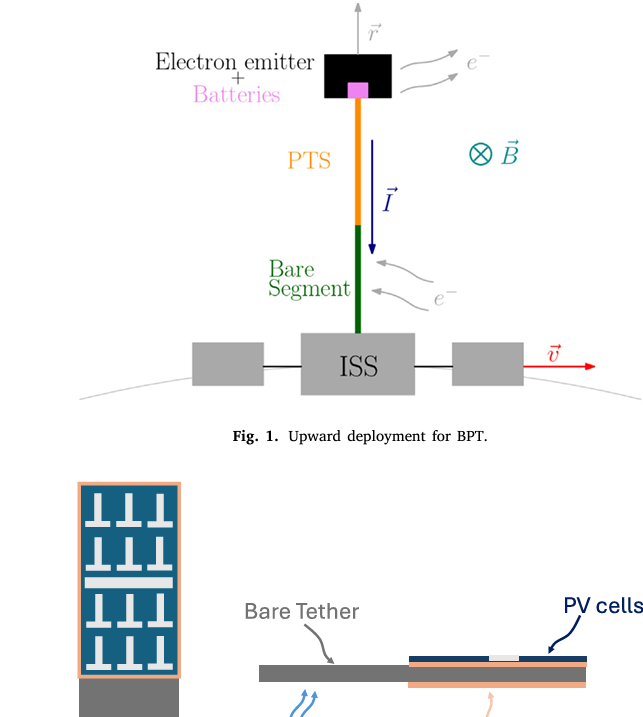

The basic idea behind BPT, and EDT more generally, is to extend a conductive boom into a magnetic field and harness the natural magnetic forces in the environment to provide propulsion. Essentially, you deploy a giant conductive rod into a magnetic field and use the force exerted by the electric field created within that rod to transmit the force to wherever the rod is connected. If the umbrella is a giant conductive rod and the wind is the Earth’s natural magnetic field, it’s like the wind picking up the umbrella.

Electrodynamic tethers are not a new concept. They were first introduced in 1968 by Giuseppe Colombo and Mario Grossi at the Harvard University Center for Astrophysics. Several demonstration missions have already flown, including TSS-1R, which launched on the Space Shuttle Atlantis in 1996 and successfully deployed a 10 km-long tether from the shuttle. Another experiment, called the Plasma Motor Generator, was conducted on the Russian space station Mir in 1999. Instead of using electromotive force to prove stationary in orbit, the experiment generated power directly from the tether itself.

Engineers have long considered using EDT to perform stationkeeping missions on the ISS. However, technical problems made it impractical. To get the right kind of force, the tether must be oriented either “downward” toward the Earth or “upward” away from the Earth.

No matter which direction the tether faces, it requires power to operate. Without a magnetic field, the current flowing through it causes it to act as an additional resistance rather than a boost. Therefore, traditional EDTs must be connected to the power system. However, if the EDT is deployed upwards of the ISS, this power system could block the approach path for capsules attempting to dock with the station.

This will require a downward facing EDT so that it can connect to the ISS power system. While this works, a previous paper published by the authors notes that downward tethers are typically used for deorbiting operations rather than accelerating them, so it’s less than ideal.

Enter BPT. The main difference from traditional EDT is that its surface is at least partially covered with solar panels. If there are enough of these solar panels, they can fully power the system and operate the upward BPT without being tied to the ISS power grid, creating an approach lane for incoming spacecraft. You can leave it empty.

Anese and his team ignored the weight of the tether and studied different options in terms of length and solar panel coverage, since the weight difference between the tether and the ISS itself was several orders of magnitude larger. They found that by using a 15km-long tether with at least 97% of one side covered with solar panels, they could counter the relatively small forces that would cause a 2km orbital descent from the ISS to the Moon.

A 15 km tether may sound like a ridiculously long time, but certainly, if it’s pointing at Earth, it would cover a relatively large percentage of the total distance to the ground. But this is well within the technological realm of possibility, especially considering that Atlantis deployed a 10 km tether some 30 years ago.

To prove their point, the authors turned to a software package called FLEXSIM. This made it possible to simulate the orbital dynamics of the ISS attached to BPTs of various lengths. The tether they chose was only 2.5 cm wide and the solar panel had an efficiency of just 4.23%, likely due to the fact that it had to be small and flexible. With this length of solar panels, the system can provide 8.3 kW of power across the tether, enough to power the ISS in orbit.

There are some subtleties about the influence of solar activity on the forces contributing to the orbital boost, but overall the system seems to work, at least in theory. However, much of the recent discussion surrounding the ISS has centered on the possibility that its lifespan may reach the end of its life as early as 2031. So while the ISS still has several years left, it likely won’t benefit much from BPT. It’s the same system as it was decades ago. That said, it is likely that someday there will be an in-orbit replacement, which could potentially benefit from such a system from the get-go, potentially saving hundreds of tons of fuel in orbit over its lifetime. There is sex.

learn more:

Anese et al – Properties of a bare solar power tether for ISS restart

UT – Tethered satellites will be able to deorbit themselves at the end of their lifespan

UT – New satellite seeks to maintain low Earth orbit without propellant

UT – SpaceX unveils enhanced Dragon that deorbits the ISS

Lead image:

Power diagram of the BPT tether system on the ISS.

Credit – Anese et al.